Thursday, November 30, 2017

The Recording Angel - James Hastings 1908

RECORDING ANGEL by James Hastings 1908

See also 125 Books on ANGELS & Angelology on DVDrom

For a list of all of my disks and ebooks (PDF and Amazon) click here

In all the early literatures of the world the angel is called upon to perform a motley variety of tasks. The universe was recognized to be the scene of a ceaseless divine activity. But it puzzled men to know how God, who was pure spirit and infinite, could come into actual contact with matter, which was impure, imperfect, and finite. Hence arose the notion of the angel, a kind of offshoot of the divine, a being semi-human and semi-divine, standing on a lower rung of divinity than the Deity, mingling freely with earthly creations and exercising over them an influence bearing the strongest resemblance to that which came directly from the Deity. The angel, in other words, bridged the yawning gulf between the world and God. It follows from this that, as the innumerable experiences of man during life and after death were subject to angelic influences, the latter had, in the imagination of early peoples, to be pigeon-holed into separate and independent departments of activity. Each angel had its own specialized task to see to, and each religion particularized those tasks in its own way. The idea of a recording angel charged with a peculiar task of its own and bearing a distinct name or series of names figures in Judaism, Christianity, and Muhammadanism. The function which it performs is, in the main, identical in all the three religious systems, but the details vary considerably.

In Judaism the work of the recording angel is that of keeping an account of the deeds of individuals and nations, in order to present the record at some future time before man's heavenly Maker. The presentation of this record may take place during the lifetime of the individual or nation, or, as is more often the case, after death; and upon this record depends either the bliss or the pain which is to be apportioned in the after life. In the OT there are three passages which form a basis for these ideas. In Mal 3:16 it is said: 'Then they that feared the Lord spake one with another: and the Lord hearkened, and heard, and a book of remembrance was written before him, for them that feared the Lord, and that thought upon his name.' Jahweh hears what His righteous servants say and resolves to reward them at some future time for their steadfastness. The figure of speech is derived from the custom of Persian monarchs, who had the names of public benefactors inscribed in a book, in order that in due time they might be suitably rewarded. In Ezk 9:4 the man 'clothed in linen which had the writer's inkhorn by his side,' is bidden to 'go through the midst of the city, through the midst of Jerusalem, and set a mark upon the foreheads of the men that sigh and that cry for all the abominations that be done in the midst thereof.' This man 'clothed in linen' is one of the six angels sent to exact speedy punishment upon the defiant city of Jerusalem. But the punishment must be discriminating. While the unrepenting are to be slain without mercy, the angel was to 'set a mark' on those who expressed sincere grief for their backslidings and who dissociated themselves from the sinners. This mark was, presumably, to serve as a reference on the day when retribution would be meted out. The third passage is Dn 12:1: 'And at that time shall Michael stand up, . . . and there shall be a time of trouble . . . and at that time thy people shall be delivered, every one that shall be found written in the book.' When this is read in connexion with the succeeding verses, the underlying idea seems clearly that of some future divine judgment when the righteous classes and the wicked classes will each reap their deserts, and the record of 'who's who' will be found written in 'the book,' the angel Michael acting as recorder.

As R. H. Charles puts it, 'the book was "the book of life" . . . a register of the actual citizens of the theocratic community on earth. . . . This book has thus become a register of the citizens of the coming kingdom of God, whether living or departed.'

A rabbi of the Mishnaic epoch, Akiba ben Joseph, summarized and elaborated all these OT conceptions of the account between man and his Maker (without, however, introducing the idea of the recording angel) in a remarkably striking parable, thus:

'Everything is given on pledge and a net is spread for all the living. The shop is open and the dealer gives credit; and the ledger lies open; and the hand writes; and whosoever wishes to borrow may come and borrow; but the collectors regularly make their daily round and exact payment from man whether he be content or not; and they have that whereon they can rely in their demand; and the judgment is a judgment of truth, and everything is prepared for the feast' (Mishnah, Aboth, iii. 16).

The 'feast' refers to the leviathan, on the flesh of which, according to a frequent idea of the Talmud and Midrash, the righteous Israelites will regale themselves in the beyond.

The rich angelologies of the Jews and Christians (as well as of the Muhammadans, who borrowed largely from the OT and the rabbinic writings) built further on these OT references to a recording angel, and transferred the work of recording to some one or other angel bearing a special name, the Deity becoming merely the recipient of the record. In rabbinic theology and in the mysticism of the Zohar and mediaeval Kabbalah generally, the recording angel is kept particularly busy in one great department of activity—viz. prayer. Metatron usually plays this role. According to a statement in Midrash Tanhuma Genesis, as well as in the Slavonic Book of Enoch, it is the angel Michael, originally the guardian-angel of Israel, who was transformed into Metatron, the angel 'whose name is like that of his divine Master' —a piece of doctrine which may possibly have influenced the Christian doctrine of the Logos. So impressive was the work of Metatron that a rabbi of the early 2nd cent. A.D., Elisha b. Abuyah, confessed to seeing this angel in the heavens and thus being led to believe that the cosmos was ruled by 'two powers.' Of course such belief was heresy. According to a Talmudic statement, Metatron bears the Tetragrammaton in himself. This was derived from Ex 23:21, where it is said of the angel who would in the future be sent to prepare the way for the Israelites" 'Beware of him . . . for my name is in him.'

According to a passage in the Zohar (Midrash Ha-Ne'el-am on section Haye-Sarah), Metatron 'is appointed to take charge of the soul every day and to provide it with the necessary light from the Divine, according: as be Is commanded. It Is he who is detailed to take the record in the grave-yards from Dumah, the angel of death, and to show it to the Master. It is he who is destined to put the leaven into the bones that lie beneath the earth, to repair the bodies and bring them to a state of perfection in the absence of the soul which will be sent by God to its appointed place (i.e. the Holy Land where they will again be put into bodies, which have come thither through a process of terrestrial transmigration—a favourite idea of some rabbinic theologians).'

The Book of Jubilees speaks of Enoch as 'the heavenly scribe.' A similar description is applied to Metatron in T.B. Hagigah, 15a, where he is designated as 'he to whom authority is given to sit down and write the merits of Israel.' In the Jerusalem Targum to Gn 5:24 'And Enoch walked with God: and he was not; for God took him,' the rendering is 'And he called his name [i.e. Enoch's] Metatron, the great scribe.' In Targum Jonathan to Ex 24:1 'And he said unto Moses, Come up unto the Lord,' the paraphrase runs 'And unto Moses, Michael the archangel of wisdom said, on the seventh day of the month, Come up unto the Lord'; while in Ascensio Isaice, ix. 21, it is Michael who is honoured with the name of heavenly scribe. From these various references one readily infers that Metatron, Enoch, and Michael were names given to angels who were pre-eminent in the realms of wisdom or scholarship, and who would, as such, be best qualified to act as 'scribes' or 'recorders' of men's deeds.

Passages in the Qur'an bear out this view of a special 'scholarly' angel who writes down the record of men. In surah ii. the role is given to Gabriel, who was so great an adept in the work that the act of writing down the Qur'an for Muhammad's benefit was actually ascribed to him. Man's work on earth and God's work in heaven were brought into touch with one another by the scholarly recording activities of Gabriel. In surah 1. another view is propounded.

'When the two angels deputed to take account of a man's behaviour take account thereof; one sitting on the right hand, the other on the left: he uttereth not a word, but there is with him a watcher ready to note it.'

Two 'recording' angels seem to be in evidence here. The meaning seems to be that, although the dying man may refuse to speak, or be unable to do so, yet the two 'recording' angels can read his inmost thoughts and take complete account of them. Sale puts quite another construction on the text, which, however, seems very far-fetched and improbable.

Quoting from the native commentary of Al-Beidawi, Sale further tells of a Muhammadan tradition to the effect that 'the angel who notes a man's good actions has the command over him who notes his evil actions; and that when a man does a good action, the angel of the right hand writes It down ten times; and when he commits an ill action the same angel says to the angel of the left hand, Forbear setting it down for seven hours; peradventure he may pray, or may ask pardon' (note on surah 1. in Sale's Koran, new ed., London, 1825, ii. 350).

The idea of the 'good' always preponderating over the 'evil' is taught abundantly in the rabbinic writings, as is also the idea of a respite ever being open to the condemned even at the eleventh hour, at the bar whether of human or of divine justice (see T.B. Ta'anith, 11a, where it is said that 'two ministering angels who accompany man, they give witness for him'). In the same passage in T.B. Ta'anith it is further said:

'When man goes to his everlasting home, all his works on earth are passed in review before him, and it is said to him. On such and such a day thou didst do such and such a deed. The man replies, Yes. Then it is said to him. Seal it (i.e. your evidence). He seals it and thus admits the justice of the Divine decree.'

Here man after death becomes his own recording angel—obviously a higher and more philosophical view.

Further references in rabbinical and apocalyptic literature are as follows:

In T.B. Megillah, 15b, the phrase In Est 6:1 about the sleepessness of the king is applied to God 'the king of the world,' who bids that 'the book of records of the Chronicles' be brought to Him. It is then found that 8himshai the scribe has erased the passage recording Mordecai's rescue of Ahasuerus, but Gabriel rewrites it 'for the merit of Israel.' Thus Gabriel becomes here a kind of national registrar. The Testament of Abraham, the Book of Jubilees, Enoch, the Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch, and 2 Esdras all speak of the day of the great Judgment, when angels and men alike will be called store the bar of justice and the book in which the deeds of men are recorded will be opened. According to the Testament of Abraham, this book in which the merits and demerits are written is ten cubits in breadth and six in thickness. Each man will be surrounded by two angels, one writing down his merits and the other his demerits, while an archangel weighs the two kinds against each other in a balance. Those whose merits and demerits are equal remain in a middle state (corresponding to the purgatory of the Church) and the Intercession of meritorious men, such as Abraham, saves them and brings them into paradise. The permanent recorder is Enoch, 'the teacher of heaven and earth, the scribe of righteousness,' and the other two angels are assistant recorders. This is probably the origin of the Qur'an statement alluded to above.

The Pharisaic school of thought, as reflected in the Mishnah, Talmud, and the Jewish liturgy generally, transferred a great deal of the eschatological connotations of the recording angel to man's temporal life on earth. Whilst admitting that man will be judged and his record taken in a hereafter, the rabbis taught that on the Jewish New Year's Day (Rosh Ha-Shanah, the first day of Tishri) the Books of Life and Death lie open before God, who as the Recorder par excellence looks through the records which He has put down against the name of each individual throughout the course of the year and then seals each one's destiny for the coming year. The mediaeval Kabbalah has amplified this doctrine with the addition of large angelological hierarchies into which man's soul enters on New Year's Day to hear its own favourable or unfavourable record from the mouth of hosts of recording angels. But the main trend of Jewish belief is in the direction of that simple but higher faith which holds that there is but one recording angel for or against man—God.

The Intolerance of Socialists

I found this 105 year old article and it immediately made me think of conservative speakers like Ben Shapiro being shouted down and some even prevented from speaking on college campuses across the nation. We instinctively know that when a religious group practices milieu (information) control like this then that is an admission that their ideas cannot withstand scrutiny. I believe we can apply the same logic with Socialist Justice Warriors and violent Antifa groups.

From Common Cause 1912

TOLERANCE AS DEFINED BY SOCIALISTS

"If there is one principle for which all Socialists are willing to mount the barricades, it is that of "free speech" and "free assemblage." So devoted are they to this ideal that they have embodied it in their platform — so jealous are they of any seeming infringement of this Constitutional privilege that they are ready to resort to any possible means to defend this right of citizenship. If the Socialists were sincere in their espousal of the cause of free speech, we should commend them for the stand they take. The safety of a democratic nation depends upon the degree of freedom with which its citizens are permitted to discuss all problems of vital interest to the country.

Unfortunately, however, as current events prove, the Socialists have shown that they cannot be commended even upon this score, for it is impossible to read the daily papers without coming to the conclusion that "freedom," to the Socialist, means freedom to think and speak as they do.

Let anybody interfere ever so slightly with the Socialist's right to mount a soap-box and tear things into smitherines and the howl from the Socialist press will reverberate from one end of the United States to the other. So far so good, but how do the Socialists themselves act? What is the attitude that they assume toward anti-Socialist speakers, or even toward their own progenitor, the Socialist Labor Party, which still represents simon-pure Marxian Socialism in this country, and from whose hearthstone the present Socialist party eloped with "Our 'Gene" not so very long ago?

If it seemed necessary we could enumerate scores of instances that have occurred during the present campaign—instances in which the appearance of a Socialist Labor speaker on a street corner has been the signal for the precipitation of a small sized riot. Again and again members of the Socialist party have attempted to break up S. L. P. meetings, heckling the speakers with absurd questions and showering abuse upon them. We can understand why Socialist party men do net want Mr. Urban or Mr. Masterson to get the ears of the crowd. They know that the searchlight of truth and logic is fatal to their cause, and so are logical in opposing the work of the anti-Socialist soap-boxers, but why should they show the same intolerant spirit when it is the S. L. P. man—the most consistent of Marxist advocates—who is orating?

Another example of the narrow-mindedness of the average Socialist was shown on the occasion of the big mass meeting at Madison Square Garden. To take advantage of the crowd which they knew would be attracted by the appearance of the Socialist party's perpetual presidential candidate, a few members of the Mother Earth group of anarchists began to circulate advertising matter and dispose of literature in the street in front of the Garden. Did the Socialist's passion for free speech, free press and free literature assert itself in this contingency? Not to any noticeable degree! Instead, the Socialists called the police and had the anarchists forcibly suppressed.

It is such illustrative experiences as these that disclose what the Socialist party really means when it talks about tolerance. To Socialist's freedom of speech and press means free license for themselves and the despotic suppression and persecution of every person who disagrees with them. We can imagine what kind of "freedom" we should enjoy were the Socialists in power."

From Common Cause 1912

TOLERANCE AS DEFINED BY SOCIALISTS

"If there is one principle for which all Socialists are willing to mount the barricades, it is that of "free speech" and "free assemblage." So devoted are they to this ideal that they have embodied it in their platform — so jealous are they of any seeming infringement of this Constitutional privilege that they are ready to resort to any possible means to defend this right of citizenship. If the Socialists were sincere in their espousal of the cause of free speech, we should commend them for the stand they take. The safety of a democratic nation depends upon the degree of freedom with which its citizens are permitted to discuss all problems of vital interest to the country.

Unfortunately, however, as current events prove, the Socialists have shown that they cannot be commended even upon this score, for it is impossible to read the daily papers without coming to the conclusion that "freedom," to the Socialist, means freedom to think and speak as they do.

Let anybody interfere ever so slightly with the Socialist's right to mount a soap-box and tear things into smitherines and the howl from the Socialist press will reverberate from one end of the United States to the other. So far so good, but how do the Socialists themselves act? What is the attitude that they assume toward anti-Socialist speakers, or even toward their own progenitor, the Socialist Labor Party, which still represents simon-pure Marxian Socialism in this country, and from whose hearthstone the present Socialist party eloped with "Our 'Gene" not so very long ago?

If it seemed necessary we could enumerate scores of instances that have occurred during the present campaign—instances in which the appearance of a Socialist Labor speaker on a street corner has been the signal for the precipitation of a small sized riot. Again and again members of the Socialist party have attempted to break up S. L. P. meetings, heckling the speakers with absurd questions and showering abuse upon them. We can understand why Socialist party men do net want Mr. Urban or Mr. Masterson to get the ears of the crowd. They know that the searchlight of truth and logic is fatal to their cause, and so are logical in opposing the work of the anti-Socialist soap-boxers, but why should they show the same intolerant spirit when it is the S. L. P. man—the most consistent of Marxist advocates—who is orating?

Another example of the narrow-mindedness of the average Socialist was shown on the occasion of the big mass meeting at Madison Square Garden. To take advantage of the crowd which they knew would be attracted by the appearance of the Socialist party's perpetual presidential candidate, a few members of the Mother Earth group of anarchists began to circulate advertising matter and dispose of literature in the street in front of the Garden. Did the Socialist's passion for free speech, free press and free literature assert itself in this contingency? Not to any noticeable degree! Instead, the Socialists called the police and had the anarchists forcibly suppressed.

It is such illustrative experiences as these that disclose what the Socialist party really means when it talks about tolerance. To Socialist's freedom of speech and press means free license for themselves and the despotic suppression and persecution of every person who disagrees with them. We can imagine what kind of "freedom" we should enjoy were the Socialists in power."

For a list of all of my disks and ebooks (PDF and Amazon) click here

Wednesday, November 29, 2017

Aquinas, Augustine and the Illusion of Time

See also Over 320 Books on DVDrom on Thinkers and Philosophy (Logic etc) and 215 Books on Christian and Bible Theology on DVDrom

Join my Facebook Group

Join my Facebook Group

Aquinas, Augustine and the Illusion of Time

From Augustine F. Hewit D.D.

It is an illusion of the imagination to conceive of time as having existed before creation. "In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth." That beginning was the first moment of time, which St. Thomas says God created when he created the universe. Time is a mere relation of finite entities to each other and to infinite being, arising from their limitation. The procession of created existences is necessarily in time, and could not have begun ab aeterno without a series actually infinite, which is impossible. Nevertheless, the first instant of created time had no created time behind it, and no series of instants behind it, intervening between it and eternity, but touched immediately on eternity.

...................................

From James Lindsay D.D.

As to the world, Aquinas says reason cannot apodictically show that the world was made in time. The eternity of creation he does not affirm, though he does not think it can be refuted, so repugnant to reason is a beginning of created things. He allows that the philosophers have been able to recognize the first thing, but denies that they have, independently of faith and by use of their reason, been able to demonstrate that creation took place in time. Saint Thomas avers that the most universal causes produce the most universal effects, and the most universal effect, he thinks, is being. There is no impression which the mind more fundamentally gathers, in the view of Aquinas, from the object than that of being. This idea of being is the first of all first principles, and may be expressed in the negative formula, "Being is not not-being." Then being, he argues, must be the proper effect of the first and most universal cause, which is God. Creation is to him properly the work of God, who produces being absolutely. And the visible world is created after ideas that are externally existent in the Divine Mind, such ideas being of the essence of God—yea, being, in fact, God. But the separateness of God from the creation has to be softened down, and this is effected by Aquinas through insisting on God as being in all things by his presence and power. When his First Cause— which, we have seen, he conceives as actus purus—has been obtained, he must needs endow Him with attributes which will explain particular effects in nature and in man. He makes God one, personal, spiritual, clothes him with perfect goodness, truth, will, intelligence, love, and other attributes. The world of effects he thinks is yet like him, though they are distinct; for the effect resembles the cause, and the cause is, in sense, in the effect. Aquinas starts from created beings in his mode of rising to God. He has a stringent definition of creation as "a production of a thing according to its whole substance" (productio alien jus rei secundum suam totam substantiam), to which is significantly added, "nothing being presupposed, whether created or increate" (nullo praeposito, quod sit vel increatum vel ab aliquo creatum). Creation, that is to say, is the production of being in itself, independently of matter as subject. He distinguishes causality which is creative from causality which is merely alterative. He recognizes non-being as before being. Creation is to Aquinas the "primary action" (prima action, possible to the "primary agent" (agens primum) alone. Material form for him depends on primary matter, being consequent on the change produced by efficient cause. And Aquinas has much to say of the rapports between substance and its accidents, and of form as that by which a thing is what it is. Intelligence, he expressly says, knows being absolutely, and without distinction of time.

................................

From Saint Augustine

What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.

................................

From James Orr

Creation for the beginning of motion within it. and Evolu- Of the original creative action, lying tion beyond mortal ken or human observation, science—as concerned only with the manner of the process—is obviously in no position to speak. Creation may, in an important sense, be said not to have taken place in time, since time cannot be posited prior to the existence of the world. The difficulties of the ordinary hypothesis of a creation in time can never be surmounted, so long as we continue to make eternity mean simply indefinitely prolonged time. Augustine was, no doubt, right when, from the human standpoint, he declared that the world was not made in time, but with time. Time is itself a creation simultaneous with, and conditioned by, world-creation and movement.

From Augustine F. Hewit D.D.

It is an illusion of the imagination to conceive of time as having existed before creation. "In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth." That beginning was the first moment of time, which St. Thomas says God created when he created the universe. Time is a mere relation of finite entities to each other and to infinite being, arising from their limitation. The procession of created existences is necessarily in time, and could not have begun ab aeterno without a series actually infinite, which is impossible. Nevertheless, the first instant of created time had no created time behind it, and no series of instants behind it, intervening between it and eternity, but touched immediately on eternity.

...................................

From James Lindsay D.D.

As to the world, Aquinas says reason cannot apodictically show that the world was made in time. The eternity of creation he does not affirm, though he does not think it can be refuted, so repugnant to reason is a beginning of created things. He allows that the philosophers have been able to recognize the first thing, but denies that they have, independently of faith and by use of their reason, been able to demonstrate that creation took place in time. Saint Thomas avers that the most universal causes produce the most universal effects, and the most universal effect, he thinks, is being. There is no impression which the mind more fundamentally gathers, in the view of Aquinas, from the object than that of being. This idea of being is the first of all first principles, and may be expressed in the negative formula, "Being is not not-being." Then being, he argues, must be the proper effect of the first and most universal cause, which is God. Creation is to him properly the work of God, who produces being absolutely. And the visible world is created after ideas that are externally existent in the Divine Mind, such ideas being of the essence of God—yea, being, in fact, God. But the separateness of God from the creation has to be softened down, and this is effected by Aquinas through insisting on God as being in all things by his presence and power. When his First Cause— which, we have seen, he conceives as actus purus—has been obtained, he must needs endow Him with attributes which will explain particular effects in nature and in man. He makes God one, personal, spiritual, clothes him with perfect goodness, truth, will, intelligence, love, and other attributes. The world of effects he thinks is yet like him, though they are distinct; for the effect resembles the cause, and the cause is, in sense, in the effect. Aquinas starts from created beings in his mode of rising to God. He has a stringent definition of creation as "a production of a thing according to its whole substance" (productio alien jus rei secundum suam totam substantiam), to which is significantly added, "nothing being presupposed, whether created or increate" (nullo praeposito, quod sit vel increatum vel ab aliquo creatum). Creation, that is to say, is the production of being in itself, independently of matter as subject. He distinguishes causality which is creative from causality which is merely alterative. He recognizes non-being as before being. Creation is to Aquinas the "primary action" (prima action, possible to the "primary agent" (agens primum) alone. Material form for him depends on primary matter, being consequent on the change produced by efficient cause. And Aquinas has much to say of the rapports between substance and its accidents, and of form as that by which a thing is what it is. Intelligence, he expressly says, knows being absolutely, and without distinction of time.

................................

From Saint Augustine

What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.

................................

From James Orr

Creation for the beginning of motion within it. and Evolu- Of the original creative action, lying tion beyond mortal ken or human observation, science—as concerned only with the manner of the process—is obviously in no position to speak. Creation may, in an important sense, be said not to have taken place in time, since time cannot be posited prior to the existence of the world. The difficulties of the ordinary hypothesis of a creation in time can never be surmounted, so long as we continue to make eternity mean simply indefinitely prolonged time. Augustine was, no doubt, right when, from the human standpoint, he declared that the world was not made in time, but with time. Time is itself a creation simultaneous with, and conditioned by, world-creation and movement.

For a list of all of my disks and ebooks (PDF and Amazon) click here

Tuesday, November 28, 2017

The Haunted Tree by Eleanor Lewis 1904

THE VENGEANCE OF A TREE BY ELEANOR F. LEWIS 1904

Join my Facebook Group

See also Forgotten Tales of Ghosts and Hauntings - 100 Books on CDrom

THROUGH the windows of Jim Daly’s saloon, in the little town of C___, the setting sun streamed in yellow patches, lighting up the glasses scattered on the tables and the faces of several men who were gathered near the bar. Farmers mostly they were, with a sprinkling of shopkeepers, while prominent among them was the village editor, and all were discussing a startling piece of news that had spread through the town and its surroundings. The tidings that Walter Stedman, a laborer on Albert Kelsey’s ranch, had assaulted and murdered his employer’s daughter, had reached them, and had spread universal horror among the people.

A farmer declared that he had seen the deed committed as he walked through a neighboring lane, and, having always been noted for his cowardice, instead of running to the girl’s aid, had hailed a party of miners who were returning from their mid-day meal through a field near by. When they reached the spot, however, where Stedman (as they supposed) had done his black deed, only the girl lay there, in the stillness of death. Her murderer had taken the opportunity to fly. The party had searched the woods of the Kelsey estate, and just as they were nearing the house itself the appearance of Walter Stedman, walking in a strangely unsteady manner toward it, made them quicken their pace.

He was soon in custody, although he had protested his innocence of the crime. He said that he had just seen the body himself on his way to the station, and that when they had found him he was going to the house for help. But they had laughed at his story and had flung him into the tiny, stifling calaboose of the town.

What were their proofs? Walter Stedman, a young fellow of about twenty-six, had come from the city to their quiet town, just when times were at their hardest, in search of work. The most of the men living in the town were honest fellows, doing their work faithfully, when they could get it, and when they had socially asked Stedman to have a drink with them, he had refused in rather a scornful manner. “That infernal city chap,” he was called, and their hate and envy increased in strength when Albert Kelsey had employed him in preference to any of themselves. As time went on, the story of Stedman’s admiration for Margaret Kelsey had gone afloat, with the added information that his employer’s daughter had repulsed him, saying that she would not marry a common laborer. So Stedman, when this news reached his employer’s ears, was discharged, and this, then, was his revenge! For them, these proofs were sufficient to pronounce him guilty.

Yet that afternoon, as Stedman, crouched on the floor of the calaboose, grew hopeless in the knowledge that no one would believe his story, and that his undeserved punishment would be swift and sure, a tramp, boarding a freight car several miles from the town, sped away from the spot where his crime had been committed, and knew that forever its shadow would follow him.

From the tiny window of his prison Walter Stedman could see the red glow of the heavens that betokened the setting of the sun. So the red sun of his life was soon to set, a life that had been innocent of all crime, and that now was to be ended for a deed that he had never committed. Most prominent of all the visions that swept through his mind was that of Margaret Kelsey, lying as he had first found her, fresh from the hands of her murderer. But there was another of a more tender nature. How long he and Margaret had tried to keep their secret, until Walter could be promoted to a higher position, so that he could ask for her hand with no fear of the father’s antagonism! Then came the remembrance of an afternoon meeting between the two in the woods of the Kelsey estate—how, just as they were parting, Walter had heard footsteps near them, and, glancing sharply around, saw an evil, scowling, murderous face peering through the brush. He had started toward it, but the owner of the countenance had taken himself hurriedly off.

The gossiping townspeople had misconstrued this romance, and when Albert Kelsey had heard of this clandestine meeting from the man who was later on to appear as a leader of the mob, and that he had discharged Stedman, they had believed that the young man had formally proposed and had been rejected. But justice had gone wrong, as it had done innumerable times before, and will again. An innocent man was to be hanged, even without the comfort of a trial, while the man who was guilty was free to wander where he would.

That autumn night the darkness came quickly, and only the stars did their best to light the scene. A body of men, all masked, and having as a leader one who had ever since Stedman’s arrival in town, cherished a secret hatred of the young man, dragged Stedman from the calaboose and tramped through the town, defying all, defying even God himself. Along the highway, and into Farmer Brown’s “cross cut,” they went, vigilantly guarding their prisoner, who, with the lanterns lighting up his haggard face, walked among them with the lagging step of utter hopelessness.

“That’s a good tree,” their leader said, presently, stopping and pointing out a spreading oak; when the slipknot was adjusted and Stedman had stepped on the box, he added: “If you’ve got anything to say, you’d better say it now.”

“I am innocent, I swear before God,” the doomed man answered; “I never took the life of Margaret Kelsey.”

“Give us your proof,” jeered the leader, and when Stedman kept a despairing silence, he laughed shortly.

“Ready, men!” he gave the order. The box was kicked aside, and then—only a writhing body swung to and fro in the gloom.

In front of the men stood their leader, watching the contortions of the body with silent glee. “I’ll tell you a secret, boys,” he said suddenly. “I was after that poor murdered girl myself. A damn little chance I had; but, by God, he had just as little!”

A pause—then: “He’s shunted this earth.

Cut him down, you fellows!”

--------------------------------------

“It’s no use, son. I’ll give up the blasted thing as a bad job. There’s something queer about that there tree. Do you see how its branches balance it? We have cut the trunk nearly in two, but it won’t come down. There’s plenty of others around; we’ll take one of them. If I’d a long rope with me I’d get that tree down, and yet the way the thing stands it would be risking a fellow’s life to climb it. It’s got the devil in it, sure.”

So old Farmer Brown shouldered his axe and made for another tree, his son following. They had sawed and chopped and chopped and sawed, and yet the tall white oak, with its branches jutting out almost as regularly as if done by the work of a machine, stood straight and firm.

Farmer Brown, well known for his weak, cowardly spirit, who in beholding the murder of Albert Kelsey’s daughter, had in his fright mistaken the criminal, now in his superstition let the oak stand, because its well-balanced position saved it from falling, when other trees would have been down. And so this tree, the same one to which an innocent man had been hanged, was left—for other work.

It was a bleak, rainy night—such a night as can be found only in central California. The wind howled like a thousand demons, and lashed the trees together in wild embraces. Now and then the weird “hoot, hoot!” of an owl came softly from the distance in the lulls of the storm, while the barking of coyotes woke the echoes of the hills into sounds like fiendish laughter.

In the wind and rain a man fought his path through the bush and into Farmer Brown‘s “cross cut,” as the shortest way home. Suddenly he stopped, trembling, as if held by some unseen impulse. Before him rose the white oak, wavering and swaying in the storm.

“Good God! it’s the tree I swung Stedman from!” he cried, and a strange fear thrilled him.

His eyes were fixed on it, held by some undefinable fascination. Yes, there on one of the longest branches a small piece of rope still dangled. And then, to the murderer’s excited vision, this rope seemed to lengthen, to form at the end into a slipknot, a knot that encircled a purple neck, while below it writhed and swayed the body of a man!

“Damn him!” he muttered, starting toward the hanging form, as if about to help the rope in its work of strangulation; “will he forever follow me? And yet he deserved it, the black-hearted villain! He took her life_________”

He never finished the sentence. The white oak, towering above him in its strength, seemed to grow like a frenzied, living creature. There was a sudden splitting sound, then came a crash, and under the fallen tree lay Stedman’s murderer, crushed and mangled.

From between the broken trunk and the stump that was left, a gray, dim shape sprang out, and sped past the man’s still form, away into the wild blackness of the night.

For a list of all of my disks and ebooks PDF and Amazon) click here

How the Viking Sagas Came About

For a list of all of my digital books and disks click here

Iceland is a little country far north in the cold sea. Men found it and went there to live more than a thousand years ago. During the warm season they used to fish and make fish-oil and hunt sea-birds and gather feathers and tend their sheep and make hay. But the winters were long and dark and cold. Men and women and children stayed in the house and carded and spun and wove and knit. A whole family sat for hours around the fire in the middle of the room. That fire gave the only light. Shadows flitted in the dark corners. Smoke curled along the high beams in the ceiling. The children sat on the dirt floor close by the fire. The grown people were on a long narrow bench that they had pulled up to the light and warmth. Everybody's hands were busy with wool. The work left their minds free to think and their lips to talk. What was there to talk about? The summer's fishing, the killing of a fox, a voyage to Norway. But the people grew tired of this little gossip. Fathers looked at their children and thought:

"They are not learning much. What will make them brave and wise? What will teach them to love their country and old Norway? Will not the stories of battles, of brave deeds, of mighty men, do this?"

So, as the family worked in the red fire-light, the father told of the kings of Norway, of long voyages to strange lands, of good fights. And in farmhouses all through Iceland these old tales were told over and over until everybody knew them and loved them. Some men could sing and play the harp. This made the stories all the more interesting. People called such men "skalds," and they called their songs "sagas."

Every midsummer there was a great meeting. Men from all over Iceland came to it and made laws. During the day there were rest times, when no business was going on. Then some skald would take his harp and walk to a large stone or a knoll and stand on it and begin a song of some brave deed of an old Norse hero. At the first sound of the harp and the voice, men came running from all directions, crying out:

"The skald! The skald! A saga!"

They stood about for hours and listened. They shouted applause. When the skald was tired, some other man would come up from the crowd and sing or tell a story. As the skald stepped down from his high position, some rich man would rush up to him and say:

"Come and spend next winter at my house. Our ears are thirsty for song."

So the best skalds traveled much and visited many people. Their songs made them welcome everywhere. They were always honored with good seats at a feast. They were given many rich gifts. Even the King of Norway would sometimes send across the water to Iceland, saying to some famous skald:

"Come and visit me. You shall not go away empty-handed. Men say that the sweetest songs are in Iceland. I wish to hear them."

These tales were not written. Few men wrote or read in those days. Skalds learned songs from hearing them sung. At last people began to write more easily. Then they said:

"These stories are very precious. We must write them down to save them from being forgotten."

After that many men in Iceland spent their winters in writing books. They wrote on sheepskin; vellum, we call it. Many of these old vellum books have been saved for hundreds of years, and are now in museums in Norway. Some leaves are lost, some are torn, all are yellow and crumpled. But they are precious. They tell us all that we know about that olden time. There are the very words that the men of Iceland wrote so long ago—stories of kings and of battles and of ship-sailing.

"They are not learning much. What will make them brave and wise? What will teach them to love their country and old Norway? Will not the stories of battles, of brave deeds, of mighty men, do this?"

So, as the family worked in the red fire-light, the father told of the kings of Norway, of long voyages to strange lands, of good fights. And in farmhouses all through Iceland these old tales were told over and over until everybody knew them and loved them. Some men could sing and play the harp. This made the stories all the more interesting. People called such men "skalds," and they called their songs "sagas."

Every midsummer there was a great meeting. Men from all over Iceland came to it and made laws. During the day there were rest times, when no business was going on. Then some skald would take his harp and walk to a large stone or a knoll and stand on it and begin a song of some brave deed of an old Norse hero. At the first sound of the harp and the voice, men came running from all directions, crying out:

"The skald! The skald! A saga!"

They stood about for hours and listened. They shouted applause. When the skald was tired, some other man would come up from the crowd and sing or tell a story. As the skald stepped down from his high position, some rich man would rush up to him and say:

"Come and spend next winter at my house. Our ears are thirsty for song."

So the best skalds traveled much and visited many people. Their songs made them welcome everywhere. They were always honored with good seats at a feast. They were given many rich gifts. Even the King of Norway would sometimes send across the water to Iceland, saying to some famous skald:

"Come and visit me. You shall not go away empty-handed. Men say that the sweetest songs are in Iceland. I wish to hear them."

These tales were not written. Few men wrote or read in those days. Skalds learned songs from hearing them sung. At last people began to write more easily. Then they said:

"These stories are very precious. We must write them down to save them from being forgotten."

After that many men in Iceland spent their winters in writing books. They wrote on sheepskin; vellum, we call it. Many of these old vellum books have been saved for hundreds of years, and are now in museums in Norway. Some leaves are lost, some are torn, all are yellow and crumpled. But they are precious. They tell us all that we know about that olden time. There are the very words that the men of Iceland wrote so long ago—stories of kings and of battles and of ship-sailing.

For more go to Norse Mythology and Viking Legends - 115 Books on DVDrom and Over 250 Books on DVDrom on Mythology, Gods and Legends

For a list of all of my digital books and disks click here

For a list of all of my digital books and disks click here

Monday, November 27, 2017

Pascal's Wager in his Own Words

See also 215 Books on Christian and Bible Theology on DVDrom or Does God Exist? - 300 Books on DVDrom (Philosophy, Apologetics)

Pascal's Wager in his Own Words

If there be a God, he is infinitely incomprehensible, since having neither parts nor limits he has no relation to us. We are then incapable of knowing either what he is or if he is. This being so, who will dare to undertake the solution of the question? Not we, who have no relation to him.

Who then will blame Christians for not being able to give a reason for their faith; those who profess a religion for which they cannot give a reason? They declare in putting it forth to the world that it is a foolishness, stultitiam, and then you complain that they do not prove it. Were they to prove it they would not keep their word, it is in lacking proof that they are not lacking in sense.—Yes, but although this excuses those who offer it as such, and takes away from them the blame of putting it forth without reason, it does not excuse those who receive it.—Let us then examine this point, and say "God is, or he is not." But to which side shall we incline? Reason can determine nothing about it. There is an infinite gulf fixed between us. A game is playing at the extremity of this infinite distance in which heads or tails may turn up. What will you wager? There is no reason for backing either one or the other, you cannot reasonably argue in favor of either.

Do not then accuse of error those who have already chosen, for you know nothing about it.—No, but I blame them for having made, not this choice, but a choice, for again both the man who calls 'heads' and his adversary are equally to blame, they are both in the wrong; the true course is not to wager at all.—

Yes, but you must wager; this depends not on your will, you are embarked in the affair. Which will you choose? Let us see. Since you must choose, let us see which least interests you. You have two things to lose, truth and good, and two things to stake, your reason and your will, your knowledge and your happiness; and your nature has two things to avoid, error and misery. Since you must needs choose, your reason is no more wounded in choosing one than the other. Here is one point cleared up, but what of your happiness? Let us weigh the gain and the loss in choosing heads that God is. Let us weigh the two cases: if you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager then unhesitatingly that he is.—You are right. Yes, I must wager, but I may stake too much.—Let us see. Since there is an equal chance of gain and loss, if you had only to gain two lives for one, you might still wager. But were there three of them to gain, you would have to play, since needs must that you play, and you would be imprudent, since you must play, not to chance your life to gain three at a game where the chances of loss or gain are even. But there is an eternity of life and happiness. And that being so, were there an infinity of chances of which one only would be for you, you would still be right to stake one to win two, and you would act foolishly, being obliged to play, did you refuse to stake one life against three at a game in which out of an infinity of chances there be one for you, if there were an infinity of an infinitely happy life to win. But there is here an infinity of an infinitely happy life to win, a chance of gain against a finite number of chances of loss, and what you stake is finite; that is decided. Wherever the infinite exists and there is not an infinity of chances of loss against that of gain, there is no room for hesitation, you must risk the whole. Thus when a man is forced to play he must renounce reason to keep life, rather than hazard it for infinite gain, which is as likely to happen as the loss of nothingness.

For it is of no avail to say it is uncertain that we gain, and certain that we risk, and that the infinite distance between the certainty of that which is staked and the uncertainty of what we shall gain, equals the finite good which is certainly staked against an uncertain infinite. This is not so. Every gambler stakes a certainty to gain an uncertainty, and yet he stakes a finite certainty against a finite uncertainty without acting unreasonably. It is false to say there is infinite distance between the certain stake and the uncertain gain. There is in truth an infinity between the certainty of gain and the certainty of loss. But the uncertainty of gain is proportioned to the certainty of the stake, according to the proportion of chances of gain and loss, and if therefore there are as many chances on one side as on the other, the game is even. And thus the certainty of the venture is equal to the uncertainty of the winnings, so far is it from the truth that there is infinite distance between them. So that our argument is of infinite force, if we stake the finite in a game where there are equal chances of gain and loss, and the infinite is the winnings. This is demonstrable, and if men are capable of any truths, this is one.

I confess and admit it. Yet is there no means of seeing the hands at the game?—Yes, the Scripture and the rest, etc.

—Well, but my hands are tied and my mouth is gagged: I am forced to wager and am not free, none can release me, but I am so made that I cannot believe. What then would you have me do?

True. But understand at least your incapacity to believe, since your reason leads you to belief and yet you cannot believe. Labor then to convince yourself, not by increase of the proofs of God, but by the diminution of your passions. You would fain arrive at faith, but know not the way; you would heal yourself of unbelief, and you ask remedies for it. Learn of those who have been bound as you are, but who now stake all that they possess; these are they who know the way you would follow, who are cured of a disease of which you would be cured. Follow the way by which they began, by making believe that they believed, taking the holy water, having masses said, etc. Thus you will naturally be brought to believe, and will lose your acuteness.—But that is just what I fear.—Why? what have you to lose?

But to show you that this is the right way, this it is that will lessen the passions, which are your great obstacles, etc.—

What you say comforts and delights me, etc.—If my words please you, and seem to you cogent, know that they are those of one who has thrown himself on his knees before and after to pray that Being, infinite, and without parts, to whom he submits all his own being, that you also would submit to him all yours, for your own good and for his glory, and that this strength may be in accord with this weakness.

The end of this argument.—Now what evil will happen to you in taking this side? You will be trustworthy, honorable, humble, grateful, generous, friendly, sincere, and true. In truth you will no longer have those poisoned pleasures, glory and luxury, but you will have other pleasures. I tell you that you will gain in this life, at each step you make in this path you will see so much certainty of gain, so much nothingness in what you stake, that you will know at last that you have wagered on a certainty, an infinity, for which you have risked nothing.

Or as William James writes it:

In Pascal's Thoughts there is a celebrated passage known in literature as Pascal's wager. In it he tries to force us into Christianity by reasoning as if our concern with truth resembled our concern with the stakes in a game of chance. Translated freely his words are these: You must either believe or not believe that God is — which will you do? Your human reason cannot say. A game is going on between you and the nature of things which at the day of judgment will bring out either heads or tails. Weigh what your gains and your losses would be if you should stake all you have on heads, or God's existence: if you win in such case, you gain eternal beatitude; if you lose, you lose nothing at all, If there were an infinity of chances, and only one for God in this wager, still you ought to stake your all on God; for though you surely risk a finite loss by this procedure, any finite loss is reasonable, even a certain one is reasonable, if there is but the possibility of infinite gain. Go, then, and take holy water, and have masses said; belief will come and stupefy your scruples, — Cela vous fera croire et vous abêtira. Why should you not? At bottom, what have you to lose?

If there be a God, he is infinitely incomprehensible, since having neither parts nor limits he has no relation to us. We are then incapable of knowing either what he is or if he is. This being so, who will dare to undertake the solution of the question? Not we, who have no relation to him.

Who then will blame Christians for not being able to give a reason for their faith; those who profess a religion for which they cannot give a reason? They declare in putting it forth to the world that it is a foolishness, stultitiam, and then you complain that they do not prove it. Were they to prove it they would not keep their word, it is in lacking proof that they are not lacking in sense.—Yes, but although this excuses those who offer it as such, and takes away from them the blame of putting it forth without reason, it does not excuse those who receive it.—Let us then examine this point, and say "God is, or he is not." But to which side shall we incline? Reason can determine nothing about it. There is an infinite gulf fixed between us. A game is playing at the extremity of this infinite distance in which heads or tails may turn up. What will you wager? There is no reason for backing either one or the other, you cannot reasonably argue in favor of either.

Do not then accuse of error those who have already chosen, for you know nothing about it.—No, but I blame them for having made, not this choice, but a choice, for again both the man who calls 'heads' and his adversary are equally to blame, they are both in the wrong; the true course is not to wager at all.—

Yes, but you must wager; this depends not on your will, you are embarked in the affair. Which will you choose? Let us see. Since you must choose, let us see which least interests you. You have two things to lose, truth and good, and two things to stake, your reason and your will, your knowledge and your happiness; and your nature has two things to avoid, error and misery. Since you must needs choose, your reason is no more wounded in choosing one than the other. Here is one point cleared up, but what of your happiness? Let us weigh the gain and the loss in choosing heads that God is. Let us weigh the two cases: if you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager then unhesitatingly that he is.—You are right. Yes, I must wager, but I may stake too much.—Let us see. Since there is an equal chance of gain and loss, if you had only to gain two lives for one, you might still wager. But were there three of them to gain, you would have to play, since needs must that you play, and you would be imprudent, since you must play, not to chance your life to gain three at a game where the chances of loss or gain are even. But there is an eternity of life and happiness. And that being so, were there an infinity of chances of which one only would be for you, you would still be right to stake one to win two, and you would act foolishly, being obliged to play, did you refuse to stake one life against three at a game in which out of an infinity of chances there be one for you, if there were an infinity of an infinitely happy life to win. But there is here an infinity of an infinitely happy life to win, a chance of gain against a finite number of chances of loss, and what you stake is finite; that is decided. Wherever the infinite exists and there is not an infinity of chances of loss against that of gain, there is no room for hesitation, you must risk the whole. Thus when a man is forced to play he must renounce reason to keep life, rather than hazard it for infinite gain, which is as likely to happen as the loss of nothingness.

For it is of no avail to say it is uncertain that we gain, and certain that we risk, and that the infinite distance between the certainty of that which is staked and the uncertainty of what we shall gain, equals the finite good which is certainly staked against an uncertain infinite. This is not so. Every gambler stakes a certainty to gain an uncertainty, and yet he stakes a finite certainty against a finite uncertainty without acting unreasonably. It is false to say there is infinite distance between the certain stake and the uncertain gain. There is in truth an infinity between the certainty of gain and the certainty of loss. But the uncertainty of gain is proportioned to the certainty of the stake, according to the proportion of chances of gain and loss, and if therefore there are as many chances on one side as on the other, the game is even. And thus the certainty of the venture is equal to the uncertainty of the winnings, so far is it from the truth that there is infinite distance between them. So that our argument is of infinite force, if we stake the finite in a game where there are equal chances of gain and loss, and the infinite is the winnings. This is demonstrable, and if men are capable of any truths, this is one.

I confess and admit it. Yet is there no means of seeing the hands at the game?—Yes, the Scripture and the rest, etc.

—Well, but my hands are tied and my mouth is gagged: I am forced to wager and am not free, none can release me, but I am so made that I cannot believe. What then would you have me do?

True. But understand at least your incapacity to believe, since your reason leads you to belief and yet you cannot believe. Labor then to convince yourself, not by increase of the proofs of God, but by the diminution of your passions. You would fain arrive at faith, but know not the way; you would heal yourself of unbelief, and you ask remedies for it. Learn of those who have been bound as you are, but who now stake all that they possess; these are they who know the way you would follow, who are cured of a disease of which you would be cured. Follow the way by which they began, by making believe that they believed, taking the holy water, having masses said, etc. Thus you will naturally be brought to believe, and will lose your acuteness.—But that is just what I fear.—Why? what have you to lose?

But to show you that this is the right way, this it is that will lessen the passions, which are your great obstacles, etc.—

What you say comforts and delights me, etc.—If my words please you, and seem to you cogent, know that they are those of one who has thrown himself on his knees before and after to pray that Being, infinite, and without parts, to whom he submits all his own being, that you also would submit to him all yours, for your own good and for his glory, and that this strength may be in accord with this weakness.

The end of this argument.—Now what evil will happen to you in taking this side? You will be trustworthy, honorable, humble, grateful, generous, friendly, sincere, and true. In truth you will no longer have those poisoned pleasures, glory and luxury, but you will have other pleasures. I tell you that you will gain in this life, at each step you make in this path you will see so much certainty of gain, so much nothingness in what you stake, that you will know at last that you have wagered on a certainty, an infinity, for which you have risked nothing.

Or as William James writes it:

In Pascal's Thoughts there is a celebrated passage known in literature as Pascal's wager. In it he tries to force us into Christianity by reasoning as if our concern with truth resembled our concern with the stakes in a game of chance. Translated freely his words are these: You must either believe or not believe that God is — which will you do? Your human reason cannot say. A game is going on between you and the nature of things which at the day of judgment will bring out either heads or tails. Weigh what your gains and your losses would be if you should stake all you have on heads, or God's existence: if you win in such case, you gain eternal beatitude; if you lose, you lose nothing at all, If there were an infinity of chances, and only one for God in this wager, still you ought to stake your all on God; for though you surely risk a finite loss by this procedure, any finite loss is reasonable, even a certain one is reasonable, if there is but the possibility of infinite gain. Go, then, and take holy water, and have masses said; belief will come and stupefy your scruples, — Cela vous fera croire et vous abêtira. Why should you not? At bottom, what have you to lose?

For a list of all of my disks and ebooks (PDF and Amazon) click here

Sunday, November 26, 2017

Charles Dickens and "Great Expectations"

See also The Best Victorian Literature, Over 100 Books on DVDrom

Join my Facebook Group

Great Expectations, Dickens's tenth novel, was published in 1861, nine years before his death. As in <David Copperfield,> the hero tells his own story from boyhood. Yet in several essential points <Great Expectations> is markedly different from <David Copperfield,> and from Dickens's other novels. Owing to the simplicity of the plot, and to the small number of characters, it possesses greater unity of design. These characters, each drawn with marvelous distinctness of outline, are subordinated throughout to the central personage "Pip," whose great expectations form the pivot of the narrative.

But the element that most clearly distinguishes this novel from the others is the subtle study of the development of character through the influence of environment and circumstance. In the career of Pip, a more careful and natural presentation of personality is made than is usual with Dickens.

He is a village boy who longs to be a "gentleman." His dreams of wealth and opportunity suddenly come true. He is supplied with money, and sent to London to be educated and to prepare for his new station in life. Later he discovers that his unknown benefactor is a convict to whom he had once rendered a service. The convict, returning against the law to England, is recaptured and dies in prison, his fortune being forfeited to the Crown. Pip's great expectations vanish into thin air.

The changes in Pip's character under these varying fortunes are most skillfully depicted. He presents himself first as a small boy in the house of his dearly loved brother-in-law, Joe Gargery, the village blacksmith; having no greater ambition than to be Joe's apprentice. After a visit to the house of a Miss Havisham, the nature of his aspirations is completely changed. Miss Havisham is one of the strangest of Dickens's creations. Jilted by her lover on her wedding night, she resolves to wear her bridal gown as long as she lives, and to keep her house as it was when the blow fell upon her. The candles are always burning, the moldering banquet is always spread. In the midst of this desolation she is bringing up a beautiful little girl, Estella, as an instrument of revenge, teaching the child to use her beauty and her grace to torture men. Estella's first victim is Pip. She laughs at his rustic appearance, makes him dissatisfied with Joe and the life at the forge. When he finds himself heir to a fortune, it is the thought of Estella's scorn that keeps him from returning Joe's honest and faithful love. As a "gentleman" he plays tricks with his conscience, seeking always to excuse his false pride and flimsy ideals of position. The convict's return, and the consequent revelation of the identity of his benefactor, humbles Pip. He realizes at last the dignity of labor, and the worth of noble character. He gains a new and manly serenity after years of hard work. Estella's pride has also been humbled and her character purified by her experiences. The book closes upon their mutual love.

"I took her hand in mine, and we went out of the ruined place; and as the morning mists had risen long ago, when I first left the forge, so the evening mists were rising now, and in all the broad expanse of tranquil light they showed to me, I saw the shadow of no parting from her."

<Great Expectations> is a delightful novel, rich in humor and free from false pathos. The character of Joe Gargery, simple, tender, quaintly humorous, would alone give imperishable value to the book. Scarcely less well-drawn are Pip's termagant sister, "Mrs. Joe"; the sweet and wholesome village girl, Biddy, who becomes Joe's second wife; Uncle Pumblechook, obsequious or insolent as the person he addresses is rich or poor; Pip's friend and chum in London, the dear boy Herbert Pocket; the convict with his wistful love of Pip; bright, imperious Estella: these are of the immortals in fiction.

________________________________________________________________

Alfred Harmsworth Northcliffe: “Great Expectations,” first published as a serial in “All the Year Round,” in 1861, is one of Dickens's finest works. It is rounded off so completely and the characters are so admirably drawn that, as a finished work of art, it is hard to say where the genius of its author has surpassed it. If there is less of the exuberance of “Pickwick,” there is also less of the characteristic exaggeration of Dickens; and the pathos of the ex-convict's return is far deeper than the pathos of children's death-beds, so frequently exhibited by the author. “Great Expectations,” for all its rare qualities, has never achieved the wide popularity of the novels of Charles Dickens that preceded it. We are not generally familiar with any name in the story, as we are with at least one name in all the other novels. Yet, Pip, as a study of child-life, youth, and early manhood, is as excellent as anything in the whole range of English fiction.

For a list of all of my disks and ebooks (PDF and Amazon) click here

Join my Facebook Group

Great Expectations, Dickens's tenth novel, was published in 1861, nine years before his death. As in <David Copperfield,> the hero tells his own story from boyhood. Yet in several essential points <Great Expectations> is markedly different from <David Copperfield,> and from Dickens's other novels. Owing to the simplicity of the plot, and to the small number of characters, it possesses greater unity of design. These characters, each drawn with marvelous distinctness of outline, are subordinated throughout to the central personage "Pip," whose great expectations form the pivot of the narrative.

But the element that most clearly distinguishes this novel from the others is the subtle study of the development of character through the influence of environment and circumstance. In the career of Pip, a more careful and natural presentation of personality is made than is usual with Dickens.

He is a village boy who longs to be a "gentleman." His dreams of wealth and opportunity suddenly come true. He is supplied with money, and sent to London to be educated and to prepare for his new station in life. Later he discovers that his unknown benefactor is a convict to whom he had once rendered a service. The convict, returning against the law to England, is recaptured and dies in prison, his fortune being forfeited to the Crown. Pip's great expectations vanish into thin air.

The changes in Pip's character under these varying fortunes are most skillfully depicted. He presents himself first as a small boy in the house of his dearly loved brother-in-law, Joe Gargery, the village blacksmith; having no greater ambition than to be Joe's apprentice. After a visit to the house of a Miss Havisham, the nature of his aspirations is completely changed. Miss Havisham is one of the strangest of Dickens's creations. Jilted by her lover on her wedding night, she resolves to wear her bridal gown as long as she lives, and to keep her house as it was when the blow fell upon her. The candles are always burning, the moldering banquet is always spread. In the midst of this desolation she is bringing up a beautiful little girl, Estella, as an instrument of revenge, teaching the child to use her beauty and her grace to torture men. Estella's first victim is Pip. She laughs at his rustic appearance, makes him dissatisfied with Joe and the life at the forge. When he finds himself heir to a fortune, it is the thought of Estella's scorn that keeps him from returning Joe's honest and faithful love. As a "gentleman" he plays tricks with his conscience, seeking always to excuse his false pride and flimsy ideals of position. The convict's return, and the consequent revelation of the identity of his benefactor, humbles Pip. He realizes at last the dignity of labor, and the worth of noble character. He gains a new and manly serenity after years of hard work. Estella's pride has also been humbled and her character purified by her experiences. The book closes upon their mutual love.

"I took her hand in mine, and we went out of the ruined place; and as the morning mists had risen long ago, when I first left the forge, so the evening mists were rising now, and in all the broad expanse of tranquil light they showed to me, I saw the shadow of no parting from her."

<Great Expectations> is a delightful novel, rich in humor and free from false pathos. The character of Joe Gargery, simple, tender, quaintly humorous, would alone give imperishable value to the book. Scarcely less well-drawn are Pip's termagant sister, "Mrs. Joe"; the sweet and wholesome village girl, Biddy, who becomes Joe's second wife; Uncle Pumblechook, obsequious or insolent as the person he addresses is rich or poor; Pip's friend and chum in London, the dear boy Herbert Pocket; the convict with his wistful love of Pip; bright, imperious Estella: these are of the immortals in fiction.

________________________________________________________________

Alfred Harmsworth Northcliffe: “Great Expectations,” first published as a serial in “All the Year Round,” in 1861, is one of Dickens's finest works. It is rounded off so completely and the characters are so admirably drawn that, as a finished work of art, it is hard to say where the genius of its author has surpassed it. If there is less of the exuberance of “Pickwick,” there is also less of the characteristic exaggeration of Dickens; and the pathos of the ex-convict's return is far deeper than the pathos of children's death-beds, so frequently exhibited by the author. “Great Expectations,” for all its rare qualities, has never achieved the wide popularity of the novels of Charles Dickens that preceded it. We are not generally familiar with any name in the story, as we are with at least one name in all the other novels. Yet, Pip, as a study of child-life, youth, and early manhood, is as excellent as anything in the whole range of English fiction.

For a list of all of my disks and ebooks (PDF and Amazon) click here

Saturday, November 25, 2017

The Economics Book Your Friends Might Actually Read

Ballve - Essentials of Economics (epub)

Imagine you have a friend who is completely unfamiliar with economics. Imagine further that he says he is going to read exactly 99 pages of economics and no more. What would you suggest that he read? I submit that Faustino Ballve’s Essentials of Economics: A Brief Survey of Principles and Policies would be an excellent candidate. The book offers an admirable combination of breadth and brevity, and it delivers on everything promised in the title. The reader will come away with a brief survey of the essential principles of our beloved dismal science, a bit of familiarity with the intellectual genealogy of some of the ideas, and a handful of applications.

By the end of the book, the reader should be convinced that it is not possible to escape from economics.

At 99 pages of text, Essentials of Economics is a masterpiece of efficient communication of economic ideas. It is an ideal introduction to economic thinking for people who haven’t the time or the inclination to conquer such massive tomes as Human Action, Wealth of Nations, or Man, Economy, and State—though I suspect that the uninitiated reader with Essentials of Economics on his nightstand or e-reader for a few days will be much more likely to read further.

By the end of the book, the reader should be convinced that, in the words of Gustavo R. Velasco’s preface to the Spanish edition, “it is not possible to escape from economics.” Ballve’s method follows in the tradition of the economists working then (and now) in the tradition of Carl Menger and Ludwig von Mises. He begins from a set of very simple postulates—scarcity and action—and deduces from these a body of propositions that help us make sense of the world around us. Ballve writes with a passion and verve that makes sometimes-dry concepts come to life. In the course of ten short chapters, he explains to the reader what economics studies, how markets work, what entrepreneurs do, how income flows to factors of production, the origins of money and credit, the origins of business cycles, and the fallacies of protectionism, nationalism, socialism, and interventionism.

While reading, I was continually impressed with the problems we face as teachers, scholars, economic communicators, and citizens. Research on public opinion and public policy—like Bryan Caplan’s 2007 The Myth of the Rational Voter, for example—suggests that the fundamental problem with economic knowledge is not that many voters don’t understand the fine points, nuances, and subtleties of sophisticated macroeconomic models. Rather, from all appearances, it looks like voters take issues with the most basic ideas in economics: people respond to incentives, resources are scarce, and trade creates wealth. Without getting bombastic or unnecessarily strident, Ballve reminds us how important these principles are in a translation that absolutely sparkles.

Much of what Ballve wrote will seem obvious today, and some readers might find his criticism of econometrics somewhat dated. It is important to remember the context in which Ballve was writing. The book first appeared in Mexico in the 1950s and in English in the early 1960s. The consensus at the time, even among professional economists, was that Mises and Hayek had lost the socialist calculation debate, and Keynesian macroeconomics ruled the roost. Ballve stepped into this environment and produced a very short, power-packed volume that offers an unapologetic defense of markets and liberty that relies not on a stubborn refusal to remove ideological blinders but on a nuanced understanding of the sciences of human action.

For the uninitiated reader, it is a fantastic introduction. For the expert, it is a valuable refresher.

Speaking of which, readers familiar with Mises’s Human Action and Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations will find much in this book that they recognize; indeed, there were times when I felt like I was actually reading Mises or Smith. For the uninitiated reader, it is a fantastic introduction. For the expert, it is a valuable refresher. For everyone, it is a valuable addition to any reading list. I expect to return to my notes on it quite frequently.

In short, Essentials of Economics is a book that any economist would be proud to have written. It offers a valuable corrective to the errors that inform too many policies. If we take Ballve’s lessons to heart, we can perhaps fix some of the damage done by policies made by those who either do not understand economics or reject it outright. At the very least, we can avoid making bad situations worse. That Essentials of Economics has not received more attention than it has is curious, if not scandalous. I hope that this book can gain a wider appreciation. The world will certainly be better for it.

Art Carden

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

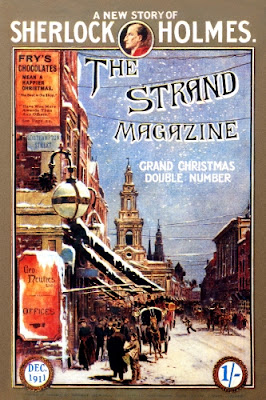

The Detective in Fiction by Arthur B Maurice 1902

The Detective in Fiction by Arthur Bartlett Maurice 1902

Join my Facebook Group

See also True Crime + Mystery Fiction - 500 Books on 2 DVDroms