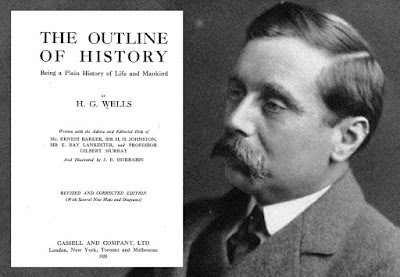

Review of The Outline of History by H.G. Wells

See also Over 200 Banned, Controversial and Forbidden Books on DVDrom and Over 200 Books that have CHANGED the World on DVDrom

Join my Facebook Group

OCCASIONALLY out of the immense volume of books annually pouring from the press there

comes one of such character as to compel your attention, and that is distinctly worth reading. To this rare class of books indubitably belongs "The Outline of History.” A really adequate review of so comprehensive a work is manifestly impossible, and one must be content with a bare indication of its scope and qualities.

In the first place, it deals with the ages before evidence of man's existence are discoverable, and traces the growth of the vegetable and animal kingdoms until man's appearance, when the rise and progress of the various civilizations are sketched in outline. The minute details of the military struggles are avoided, but enough of them is related to give the reader an understanding of their significance. It is an attempt, as the author says in his introduction, “to tell truly and clearly, in one continuous narrative, the whole story of life and mankind, so far as it is known to-day.”

This attempt is by no means a small one, and it is no faint praise to say that the author has succeeded in it.

The earlier chapters are the least fresh and interesting, not alone because they traverse familiar ground, and deal with ages about which little is certainly known, but for the further reason that the author does not appear to be at his best in handling problems which are scientific in their nature. For example, he explains the absence of man's immediate ancestor in any of the geological strata by saying that very likely this ancestor lived in the open ground, where fossil remains would not be preserved as they were in the case of submarine life. It does not seem to occur to Mr. Wells that possibly the “link” may be missing because it never existed.

But when Mr. Wells gets away from the realms of hypothesis, and begins to deal with men and nations of whose history some authentic records remain, he is on firm ground, which he treads with sure steps.

The style of the book is admirable in its simple lucidity. It is never uninteresting, and is generally candid and fair.

Some of his judgments will fail of universal acceptance, of course. He denounces Napoleon unsparingly, calling him a “brassy swindler,” and the inspirer of forgers, thieves and crooks generally. Gladstone he calls “profoundly ignorant,” but admits that it was this “profoundly ignorant” Gladstone who offered genuine home rule to Ireland for the first time in history. Dealing with our Civil War, mention is made of Lee and Sherman, but nothing is said of Grant. Lincoln he dismisses in a sentence or two. It is incomprehensible how Mr. Wells, who is scrupulously noting the rise of the people to a decisive voice in their own affairs, entirely misses the great importance which the example of Lincoln’s life afforded.

The author, except in the case of Napoleon, displays few personal animosities, though he unsparingly condemns Cato Major.

Mr. Wells tells us that history never repeats itself, a dictum which his own work strikingly and amusingly confutes. He relates how Alexander the Great had an ambition to form a League of Nations, but was forestalled in this magnificent plan by his wife, Olympias. Then when Mr. Wells comes down to the Paris Peace Conference, he says that this later proposal for a League of Nations came to nothing because the President of the United States took his wife with him to Europe. Here is a repetition of history with a vengeance.

But the principal significance of this work lies in its main thesis, which might be put in a few words as “the moral collapse of Christianity,” but which Mr.Wells may be allowed to state more fully. He says (Vol. II, p. 90):

The first thing that will strike the student is the intermittence of the efforts of the Church to establish the world City of God. The policy of the church was not wholeheartedly and continuously set upon that end. It was only now and then that some fine personality or some group of fine personalities dominated it in that direction. The Kingdom of God that Jesus of Nazareth had preached was overlaid, as we have explained, almost from the beginning by the doctrines and ceremonial traditions of an earlier age, and of an intellectually inferior type. Christianity almost from its commencement ceased to be purely prophetic and creative. It entangled itself with archaic traditions of human sacrifice, with Mithraic blood-cleansing, with priest-craft as ancient as human Society, and with elaborate doctrines about the structure of divinity. The gory finger of the Etruscan pontifex maximus emphasized the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth; the mental complexity of the Alexandrian Greek entangled them. In the inevitable jangle of these incompatibles the church had become dogmatic. In despair of other Solutions to its intellectual discords it had resolved to arbitrary authority. Its priests and bishops were more and more men moulded to creeds and dogmas and set procedures; by the time they became cardinals or popes they were usually oldish men, habituated to a politic struggle for immediate ends and no longer capable of world-wide views. They no longer wanted to see the Kingdom of God established in the hearts of men—they had forgotten about that: they wanted to see the power of the church, which was their own power, dominating men. They were Prepared to bargain even with the hates and fears and lusts in men's hearts to ensure that power.

The author's views on this subject are again thus further set forth in volume I, page 576:

This doctrine of the Kingdom of Heaven, which was the main teaching of Jesus, and which plays so small a part in the Christian creeds, is certainly one of the most revolutionary doctrines that ever stirred and changed human thought. It is small wonder that the world of that time failed to grasp its full significance, and recoiled in dismay from even a half apprehension of its tremendous challenges to the established habits and institutions of mankind. It is small wonder if the hesitating convert and disciple presently went back to the old familiar ideas of temple and altar, of fierce deity and propitiatory observance, of consecrated priest and magic blessing, and—these things being attended to—reverted then to the dear old habitual life of hates and profits and competition and pride. For the doctrine of the Kingdom of Heaven, as Jesus seems to have preached it, was no less than a bold and uncompromising demand for a complete change and cleansing of the life of our struggling race, an utter cleansing, without and within.

The ideas above expressed, and even more extreme statements of them, run through this work as a continuous thread.

That a writer of history, seeking to find an explanation for the present status of civilization, should attach so much importance to this matter, must excite the profound interest of every careful student of human affairs.

Before closing this notice, mention must be made of the scholarship it evidences. The bibliography constitutes an inviting field to the student of history.

Mr. Wells is fair and even generous in his references to the United States, for whose people and institutions he evidences a sincere liking. He points out that the Monroe Doctrine has saved the American countries from the grasping policies of the European powers.

The causes of the Great War are correctly stated. Mr. Wells does not attach great weight to the notion that the Germans displayed unusual atrocity in conducting their campaigns.

Coming down to the Peace Conference, its moral failure is emphasized. The verdict of this historian is decidedly against President Wilson, as it is likewise against the League of Nations. But Mr. Wells believes that the trend of events is toward a world unification. His concluding chapter, in which he pictures this future state, though necessarily largely imaginative, is exceedingly noble.

The author thus hopefully expresses his confidence in the world's approaching return to sanity:

Tremendously as these phantoms, the Powers, rule our minds and lines to-day, they are, as this history shows clearly, things only of the last few centuries, a mere hour, an incidental phase, in the vast deliberate history of our kind. They mark a phase of relapse, a backwater, as the rise of Machiavellian Monarchy marks a backwater; they are part of the same eddy of faltering faith, in a process altogether greater and altogether different in its general tendency, the process of the moral and intellectual reunion of mankind. For a time men have relapsed upon these national or imperial gods of theirs; it is but for a time. The idea of the world state, the universal kingdom of righteousness, of which every living soul shall be a citizen, was already in the world two thousand years ago never more to leave it. Men know that it is present even when they refuse to recognize it. In the writings and talk of men about international affairs to-day, in the current discussions of historians and political journalists, there is an effect of drunken men growing sober, and terribly afraid of growing sober. They still talk loudly of their “love” for France, of their “hatred” of Germany, of the “traditional ascendancy of Britain at sea,” and so on and so on, like those who sing in their cups in spite of the steadfast onset of sobriety and a headache. These are dead gods they serve. By sea or land men want no Powers ascendant, but only law and service, That silent unavoidable challenge is in all our minds like dawn breaking slowly, shining between the shutters of a disordered room.

Viewed merely as a history "The Outline" is a work fo first importance, As literature it is entertaining. It's greater worth lies in the clearer insight it affords of the substantial identity of interest between the different peoples of the world.

For a list of all of my disks, with links, go to https://sites.google.com/site/gdixierose/ or click here

No comments:

Post a Comment