Monday, March 7, 2016

The Detective in Fiction by Arthur Bartlett Maurice 1902

The Detective in Fiction by Arthur Bartlett Maurice 1902

Join my Facebook Group

See also True Crime + Mystery Fiction - 500 Books on 2 DVDroms

The different types of detectives in fiction may be classified according to the social scale. Old Rafferty, Chink, Sleuth, Butts, and all of that ilk may be designated as the canaille, the proletarians; Poe's Dupin, Gaboriau's Lecoq and Père Tirauclair, and Dr. Doyle's Sherlock Holmes are the patricians; they represent the grand monde: between these extremes are the detectives who belong to the bourgeoisie of detection, and they, of course, are of the greatest number. An excellent type of this middle class is the Mr. Gryce of the stories of Anna Katharine Green. A crime is committed; Mr. Gryce is appealed to; he catches the scent; and at the end of the volume he shows you that the real culprit is the person who has been before you throughout, but whom you never have thought of suspecting. This last is the very basis of the real detective story of any length. Some years ago there appeared a detective story—was it not by Professor Brander Matthews?—in which the culprit was finally detected by a camera concealed in a clock. In the course of the story every character was at some time suspected, and then cleared of suspicion, and at the end the author explained that the crime had in reality been committed by a person of whom he had never before heard. This same law for the writing of detective stories seriously impairs the interest of one of Gaboriau's best—L'Affaire Lerouge. By the time we were half through the book and long before any hint of the true state of affairs is necessary, we are forced to the inevitable conclusion of the guilt of Noel, startling as that theory seems on its face, simply because Noel is the only possible person who has consistently avoided being the object of suspicion. Of this phase of the art of constructing a detective story Mr. Gryce has had every advantage, but beyond this there is nothing of very much importance; we are ready to accept what he has done, but there is nothing extraordinary in the way he has done it, and he remains, despite his dramatic environment, comparatively commonplace.

It was in Edgar Allan Poe's Dupin that the reasoner, the intellectual sleuth, first took definite form. Poe's weird mind had seized upon some curious phases of our mental life which are with us every day, and yet which are so vague and shadowy that they are persistently ignored. He had indulged, as has every one, in the tracing of one's mind back from thought to thought, and he conceived the idea of an acute observer who should reverse the process, and by a careful analysis of character and temperament, and a close watch of such outside subjects as might have influence, accurately follow from subject to subject the workings of his neighbour's mind.

In “The Murders of the Rue Morgue” Dupin first found the opportunity to put his powers to a practical test. Two women, mother and daughter, are found in their room slain in a most revolting manner. Through a series of acute observations and deductions Dupin traces the crime to an orangoutang escaped from the custody of its master, a sailor. It is all very ingenious, but the details are so peculiar and extraordinary that the horror falls somewhat flat. But take the tale apart, and one finds a curious analogy to the methods used in the stories about Sherlock Holmes. Dupin and his historian have rooms together, just as Holmes and Watson did. In each case the curiosity of the historian is first aroused by noticing the unconventional habits and studies of his companion. Dupin has his detractors among the official police, just as Holmes has his Gregson and his Lestrade, and Lecoq his Gevrol. The advertisement of the orang-outang which Dupin puts in the Paris newspapers and which results in the visit of the sailor, has found constant imitations in the career of Sherlock Holmes. In “The Purloined Letter,” a story in which we can find much of the inspiration of “A Scandal in Bohemia” and “The Naval Treaty,” Dupin is most plausible. A letter of great political importance, involving the honour of a queen, has been stolen by her enemy, a cabinet minister. To the recovery of this letter the official police have vainly devoted all their resources. The minister has been waylaid by apparent highwaymen and his person searched. Everything in his house has been minutely examined, pictures have been unmounted, the rungs of his chairs have been bored, every cubic inch has been put to the test. As a last resort Dupin is summoned. The amateur detective mentally places himself in the position of the minister, calls at the latter's house, looks for the most obvious object as the one most likely to escape attention, and recovers the letter. Granting the premises, “The Purloined Letter” is one of the most perfect stories of its kind. Of Dupin's methods in “The Mystery of Marie Roget,” in which tale Poe developed his own theory of the murder of Mary Rogers, the beautiful cigar girl, a crime of which all New York was at the time talking, very little can be said. The editors of the magazine in which the story originally appeared decided that it would be best to omit the last half of the tale, and so far as the present writer knows “The Mystery of Marie Roget” has never been printed in full.

If in one line we can trace the ancestry of Sherlock Holmes to Edgar Allan Poe's Dupin, in another we can work back to Gaboriau, not, however, to the great Lecoq, but to old Taboret, better known to the official police who are introduced into the tales as Père Tirauclair. From Dupin, Holmes derived his intellectual acumen, his faculty of mentally placing himself in the position of another, and thereby divining that other's motives and plans, his raising of the observation of minute outward details to the dignity of an exact science. Père Tirauclair inspired him to that wide knowledge of criminal and contemporary history which enabled him to throw a light on the most puzzling problem and to find some analogy to the most outré case. With Lecoq, Holmes has absolutely nothing in common.

The deductions of Dupin and of Sherlock Holmes we are ready to accept, because we feel that it is romance, and in romance we care to refute only what seriously jars our sense of what is logical; we take those of Lecoq, because they convince beyond all question, because when one has been forced upon us, we are ready defiantly to maintain that no other is possible. To present Lecoq briefly, let us confine our attention to three books: Monsieur Lecoq, The Mystery of Orcival (Le Crime d'Orcival) and File 113 (Dossier 113). The material upon which these stories were based, as

was the case with almost all of Gaboriau's books, was taken from the secret archives of the Paris police. In Monsieur Lecoq we have the detective at the beginning of his career, a subordinate in the police service, seeking in that profession a field for his peculiar talents and his hitherto baulked ambition. One winter's night he is one of a party of police sent out to “round up” the slums of Paris. As they are traversing an open space near the southeast fortifications of the city, they hear terrible cries coming from a near-by drinking den. They break in the door, find three men dead on the floor and the murderer, with a smoking pistol in his hand, barricaded behind an overturned table. He tries to escape, but Lecoq, who has left his companions, enters the den from the rear, seizes him, and the assassin throws down his pistol, crying, “It is the Prussians who are coming!” It is on these words that the whole story is constructed. Just as at Waterloo the Emperor expected Grouchy instead of Blücher, so the murderer was looking to the quarter whence Lecoq came for an ally and not an enemy. And instantly there takes possession of the young detective's mind the belief that this grimy, unkempt ruffian is other than he seems—that he is certainly a man of education, perhaps even a man of the highest social rank. To this belief he clings throughout, in spite of every obstacle, in spite of the derision of his comrades and the open hostility of his superiors. Only once does he falter. He is very young, and the truth which is dawning upon him is so astounding. He goes for advice to Père Tirauclair; through the latter's knowledge of contemporary history his doubts are dispelled, he is shown the connecting link between the attempted suicide of the prisoner and the mysterious accident of the examining judge, and in the end he succeeds triumphantly in demonstrating that the assassin May is in reality the Duc de Sairmeuse. Sherlock Holmes rather ungraciously fleered at the whole feat, and boasted that he would have established the prisoner's identity in twenty-four hours.

In the Mystery of Orcival a terrible crime has been committed in a château near Paris. The local officials have been in charge for some hours, and have forged a very damning chain of evidence

against one of the servants of the château. Lecoq, now high in his profession, arrives and looks over the ground. One of the most important points in the evidence is a clock, which has been overturned in the struggle which has taken place and which has stopped with the hands pointing a few minutes before midnight. This apparently establishes the time at which the crime was committed. Lecoq looks at the clock; then turns the hands forward to the hour. The clock strikes three. Lecoq smiles: with a move of his finger he has upset completely the laboriously constructed theory of the local police. This is only one of many points in this book which place the cunning of Lecoq above dispute. The opening chapters of File 113 tell of the abstraction of a vast sum of money from a Paris bank. The money has been taken from a safe to which there are but two keys, one of which has been used, and on the green iron door there is a long scratch which tells of the agitation of the thief. An ambitious young detective, known as “The Squirrel,” has presumptuously attempted to cope with Lecoq and to work independently. When he is floundering hopelessly, Lecoq comes to his aid and shows how at one time “The Squirrel” had momentarily the great opportunity. “You should immediately have asked for both the keys. To the one that was used there would have adhered some of the green paint from the scratch.”

There are few, if any, men to-day who possess to so high degree as Dr. Doyle the art of weaving into their narratives episodes which are facts or of carrying their fiction to the very edge of history. This, be it understood, is said without any thought of disparagement. He himself has told how for The White Company he “tore” the very heart out of the chronicles of Froissart. His “Story of the Lost Special” was based on a story which appeared in this country a good many years ago, and to which Dr. Doyle gave an ending where the original writer thought none was possible. If, after reading Rodney Stone, you will take up Pierce Egan and other writers of the English prize-ring, you will see how old stories have been taken out of their crude setting and illuminated with the fire and colour of a real story teller. Most of the men who sat round the table at the banquet given to the Corinthians and the Fancy by Sir Charles Tregellis are as historic as the Tower, and the fight in the coach house which introduced young Jim Harrison to London was almost word for word an episode in the early career of Pierce, the Game Chicken, some time champion of England. And in some such manner, out of odds and ends, Dr. Doyle seems to have constructed the many-sided character of Sherlock Holmes.

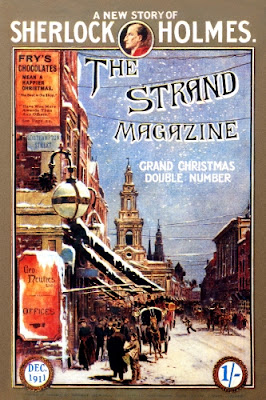

A point which for the time places Holmes by the side of Lecoq is that of the pills in The Study in Scarlet. The body of Drebber has been found in the deserted house, the story is well on its way, and Watson and the official police and the reader are floundering about in utter darkness. Lestrade comes with the tale of the murder of Stangerson, and after narrating the dramatic and relevant points enumerates the unimportant objects that have been found beside the body. At the words, “box of pills,” Holmes springs to his feet with the astounding statement that his case is complete, and begins the demonstration which ends a few minutes later with the handcuffing of the cabman. Here and there throughout the other stories there are points almost, if not equally, as telling. In “The Adventure of the Speckled Band,” perhaps the weirdest and most hideous tale that Dr. Doyle has ever written, there is a fine subtlety in the manner in which Holmes links the bed clamped to the floor, the dummy bell-rope, the ventilator, the dog whip, the saucer of milk and the clanging safe. There is ingenuity in “The Reigate Puzzle,” “The Five Orange Pips,” “The Scandal in Bohemia,” “The Naval Treaty” and “The Engineer's Thumb;” and as is told elsewhere in this number of THE BOOKMAN, an episode of much significance in the recently published The Hound of the Baskervilles. The name of Sherlock Holmes, with that of Dupin, will in the end be found very near the apex; but in the realm of material achievement Lecoq must stand alone.

For a list of all of my disks and ebooks (PDF and Amazon) click here

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment