Tuesday, January 31, 2023

Wrongfully Convicted on This Day in History

Tuesday, December 20, 2022

The Longest Prison Sentence on This Day in History

This Day in History. Richard Honeck, 84, who had served the longest prison sentence in American history, was granted parole on this day in 1963, from the Southern Illinois Penitentiary after serving 64 years incarceration. He had been incarcerated since September 2, 1899, for the brutal murder of schoolteacher Walter F. Koeller and had been eligible for parole since 1945, but had not been released because his immediate relatives had all died. On August 25, 1963, an article by Associated Press reporter Bob Poos brought the case to national attention. One of the people who read the article, Mrs. Clara Orth of San Leandro, California, agreed to take her 84-year old uncle into her home. Honeck would survive 13 more years, dying on December 28, 1976, in a nursing home at the age of 97.

The time served by Richard Honeck has been exceeded since his release in at least three cases.

Johnson Van Dyke Grigsby (1886–1987) served 66 years and 123 days at Indiana State Prison from 1908 to 1974 after stabbing a man in 1907 during a poker game/bar fight.

Joseph Ligon (1938-present) served 68 years at the State Correctional Institution – Phoenix and was at one time the oldest juvenile lifer in the US, Ligon at age 15 was sentenced in 1953 to life without parole for murder, a mandatory sentence at the time. Ligon first rejected a resentencing and parole offer in 2016. Ligon was again resentenced in 2017 and immediately eligible for parole but refused it, pending his appeal. Ligon contends that he should be resentenced to "time served" and released, so he can cut all ties to the justice system. He was released in 2021, after serving 68 years in prison.

Paul Geidel, (1894–1987) who was convicted of second-degree murder in 1911, served 68 years and 245 days in various New York state prisons. He was released on May 7, 1980, at the age of 86. Geidel's case differed from Honeck's in several key respects. First, he was initially sentenced not to life imprisonment but to twenty years to life, but was later declared insane and was incarcerated in a psychiatric hospital. Secondly, Geidel was offered parole at an earlier date than was Honeck – in 1974, when he had served only 63 years. By this time, Geidel had become institutionalized and declined release, voluntarily choosing to remain confined for an additional six years.

William Heirens, (1928–2012) the "Lipstick Killer," confessed and plead guilty to three murders in Chicago in 1946, sentenced to three life terms, and imprisoned 5 September 1946. He exceeded Honeck's record of time served in August 2010. Heirens died still incarcerated on March 5, 2012.

Monday, July 18, 2022

A Correctional Officer's Death on This Day in History

Friday, December 17, 2021

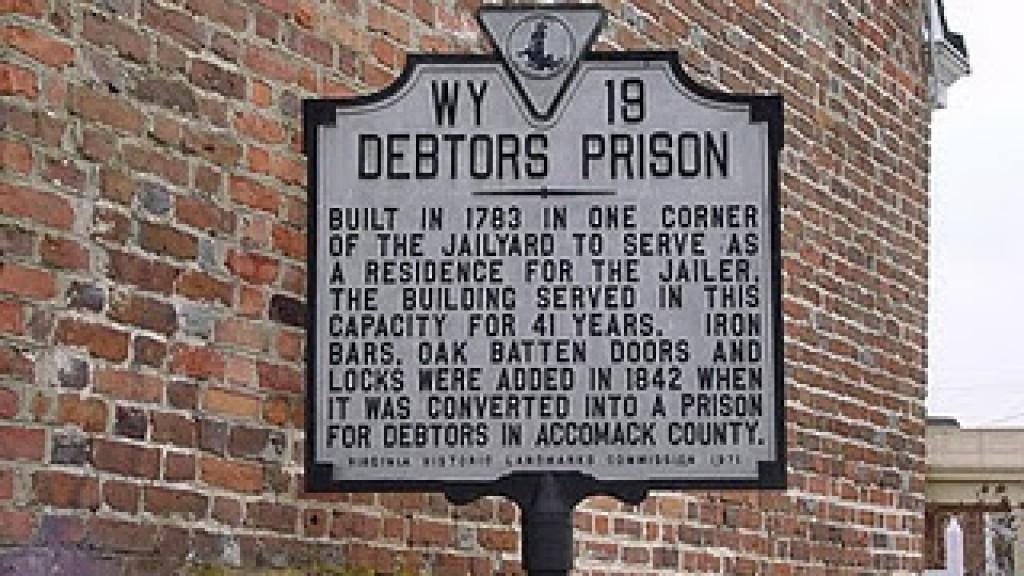

Debtors Prisons on This Day in History

This day in history: Kentucky abolished debtors prisons on this day in 1821.

A debtors' prison is a prison for people who are unable to pay debt. Through the mid-1800s, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe. Destitute persons who were unable to pay a court-ordered judgment would be incarcerated in these prisons until they had worked off their debt via labor or secured outside funds to pay the balance. The product of their labor went towards both the costs of their incarceration and their accrued debt. Increasing access and lenience throughout the history of bankruptcy law have made prison terms for unaggravated indigence obsolete over most of the world.

"Systems of debt bondage have existed for thousands of years. It was a common practice throughout Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire. A person who owed a debt could be compelled into serving their creditor for many years. These sorts of practices spun-off into debtors’ prisons in the Middle Ages, though debt bondage continued to exist and is still practiced in many parts of the world...ou’ve probably heard someone refer to jail as 'the clink.' What you may not have realized is that it’s the name of a real prison in England. The Clink was built in 1144 and was in operation for centuries. That means it housed all manner of prisoners over the years, including many debtors. Even the famous could end up in debtors’ prison. William Hughton, playwright and Shakespearean contemporary, found himself in The Clink for failing to pay back a loan from London entrepreneur Philip Henslowe." Source

Debtors Prisons in the past could be quite harsh: "The prisons were full of rats, lice and fleas. The prisoners were denied basic necessities of life such as food, water and clothing. It is said that these places were dirty and filthy that around 25% of the inmates died due to these horrible living conditions. The debtors were imprisoned and tortured at the pleasure of the creditors. When other countries of Europe had legislation limiting the debt imprisonment term to 1 year, England did not have such a law. When in 1842, the fleet prison was closed; it was found that debtors were there for more than 30 years." Source

Since the late 20th century, the term debtors' prison has also sometimes been applied by critics to criminal justice systems in which a court can sentence someone to prison over willfully unpaid criminal fees, usually following the order of a judge. For example, in some jurisdictions within the United States, people can be held in contempt of court and jailed after willful non-payment of child support, garnishments, confiscations, fines, or back taxes. Additionally, though properly served civil duties over private debts in nations such as the United States will merely result in a default judgment being rendered in absentia if the defendant willfully declines to appear by law, a substantial number of indigent debtors are legally incarcerated for the crime of failing to appear at civil debt proceedings as ordered by a judge. In this case, the crime is not indigence, but disobeying the judge's order to appear before the court. Critics argue that the "willful" terminology is subject to individual mens rea (intention) determination by a judge, rather than statute, and that since this presents the potential for judges to incarcerate legitimately indigent individuals, it amounts to a de facto "debtors' prison" system.