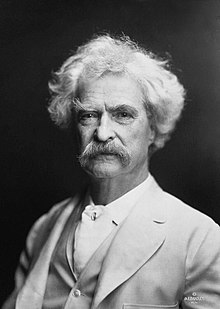

This Day in History: Samuel Langhorne Clemens, known by his pen name Mark Twain was born on this day in 1835.

Nobody expressed rugged American individualism better than Samuel Langhorne Clemens—Mark Twain.

This might seem surprising to those who think of him only as the author of children’s classics like The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Prince and the Pauper, and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. But adults going back to the books are soon reminded how they passionately affirm the moral worth of individual human beings.

A mere author of children’s books? Throughout much of Mark Twain’s life, his opinions made news because he was the most famous living American. He was a friend of steel entrepreneur Andrew Carnegie. Helen Keller, amazingly cultured despite being blind and deaf, relished his company. Mark Twain introduced future English statesman Winston S. Churchill to an American audience. He published the hugely popular autobiography of General Ulysses S. Grant. English novelist Rudyard Kipling came calling at his upstate New York home. Mark Twain met illustrious people like oil entrepreneur John D. Rockefeller, Sr., biologist Charles Darwin, painter James McNeill Whistler, psychiatrist Dr. Sigmund Freud, Waltz King Johann Strauss, violinist Fritz Kreisler, pianist Artur Schnabel, sculptor Auguste Rodin, philosophers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Herbert Spencer, playwright George Bernard Shaw, poets Alfred Lord Tennyson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, novelists Henry James and Ivan Turgenev, inventors Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison (who recorded the author’s voice).

Although Mark Twain wasn’t a systematic thinker, he was steadfast in his defense of liberty. He attacked slavery, supported black self-help. He spoke out for immigrant Chinese laborers who were exploited by police and judges. He acknowledged the miserable treatment of American Indians. He denounced anti-Semitism. He was for women’s suffrage. Defying powerful politicians like Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain spearheaded the opposition to militarism. During his last decade, he served as vice president of the Anti-Imperialist League. “I am a moralist in disguise,” he wrote, “it gets me into heaps of trouble when I go thrashing around in political questions.”

He shared the capitalist dream. He speculated in mining stocks. He started a publishing company. He functioned as a venture capitalist providing about $50,000 a year to inventors—he thought invention was perhaps the highest calling. He failed at all these and achieved financial success only as a writer and lecturer.

Mark Twain set a personal example for self-reliance. From the time he quit school at age 12, he was on his own, working as a printer’s assistant, typesetter, steamboat pilot, miner, editor, and publisher. He spent four years paying off 100 percent of his business debts rather than take advantage of limited liability laws. As a writer, he succeeded entirely on his wits, without the security of academic tenure or a government grant. He financed his extensive overseas travels by freelance writing and lecturing. During his lifetime, people bought more than a million copies of his books.

Mark Twain liked what he called “reasoned selfishness.” As he put it, “A man’s first duty is to his own conscience and honor—the party of the country come second to that, and never first. . . . It is not parties that make or save countries or that build them to greatness—it is clean men, clean ordinary citizens . . . .”

Mark Twain displayed a devilish wit. Among his most memorable lines: “What is the difference between a taxidermist and a tax collector? The taxidermist takes only your skin . . . Public servant: Persons chosen by the people to distribute the graft . . . . There is no distinctly native American criminal class except Congress . . . . In the first place, God made idiots. This was for practice. Then He made School Boards . . . In statesmanship, get the formalities right, never mind about the moralities.”

Mark Twain, Popular Hero

Mark Twain was instantly recognizable. One scholar noted that “The young man from Missouri, with drooping moustache and flaming red hair, was unusually garbed in a starched, brown linen duster reaching to his ankles, and he talked and gesticulated so much that people who did not know him thought he was always drunk.”

Mark Twain was a popular hero because people didn’t just read his works. They saw him on lecture platforms in Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia. “Mark Twain steals unobtrusively on to the platform,” wrote one reporter in April 1896, “dressed in the regulation evening clothes, with the trouser-pockets cut high up, into which he occasionally dives both hands. He bows with a quiet dignity to the roaring cheers. . . . He speaks slowly, lazily, and wearily, as a man dropping off to sleep, rarely raising his voice above a conversational tone; but it has that characteristic nasal sound which penetrates to the back of the largest building. . . . To have read Mark Twain is a delight, but to have seen and heard him is a joy not readily to be forgotten.”

Samuel Langhorne Clemens was born November 30, 1835 in Florida, Missouri. He was the fifth child of Jane Lampton, a plainspoken Kentucky woman from whom Sam reportedly acquired his compassion and sense of humor. His father John was a lanky, somber Tennessee lawyer-turned-grocer. He got wiped out speculating in land and other ventures. When Sam was four, the hapless family moved about 30 miles away to Hannibal, Missouri, a Mississippi River town. They had to sell their spoons and rent rooms above a drug store. Yet during the 14 years Sam lived in Hannibal, he gained experiences which inspired his greatest classics.

Clemens attended several schools until he was about 13, but his education really came from his mother. She taught him to learn on his own and respect the humanity of other people, including slaves.

Soon after John Clemens died in 1847, Sam went to work as a printer’s assistant. During the next decade, he worked for printers in St. Louis, New York, Philadelphia, Keokuk (Iowa), and Cincinnati. Clemens, like Benjamin Franklin, educated himself by reading through printers’ libraries. He especially loved history. The more he read, the more he reacted against intolerance and tyranny.

Back in Hannibal, he decided to master the mysteries of the Mississippi. He got a job assisting steamboat pilot Horace Bixby who, for $500 mostly deducted from wages, taught him how to navigate the roughly 1,200 miles of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and St. Louis. During the next 17 months, Clemens learned the shape of the river, the way it looked at night and in fog.

The Civil War disrupted commerce on the Mississippi, dashing his ambitions as a steamboat pilot. Eager to help the South, in 1861, he joined a company of Missouri volunteers known as the Marion Rangers. One night they shot an unarmed, innocent horseman, and the disgusted Clemens quit.

He headed for the Nevada Territory, hoping to strike it rich by finding silver. Since that didn’t happen, he wrote amusing articles about silver mining camps for Nevada’s major newspaper, the Territorial Enterprise, which was published in Virginia City. He landed a full-time job. Initially, his articles were unsigned. Then he decided that to become a literary success, he must begin signing his articles. Pseudonyms were in vogue, so he reached back to his days as a Mississippi River pilot and thought of “Mark Twain,” a term meaning two fathoms, or 12 feet—navigable water for a steamboat. His first signed article appeared February 2, 1863.

It was in Virginia City that Mark Twain met the popular humorist Artemus Ward who was on a lecture tour. His commercial success inspired Mark Twain to think about how he might make a career with his wit. Ward urged him to break into the big New York market.

He wrote his brother and sister, October 1865: “I never had but two powerful ambitions in my life. One was to be a pilot, & the other a preacher of the gospel. I accomplished the one & failed in the other, because I could not supply myself with the necessary stock in trade—i.e., religion . . . I have had a `call’ to literature, of a low order—i.e., humorous. It is nothing to be proud of, but it is my strongest suit.”

After silver mining stocks he had acquired became worthless, he resolved to make the best of humorous writing. The following year, his story, “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” was published in The New York Saturday Press, and many other publications reprinted it. Suddenly, he had a national reputation as “the wild humorist of the Pacific Slope.” The Sacramento Union asked him to report on news in Hawaii, and he was off again. He got the idea of giving public lectures about his experiences there. He rented a San Francisco hall starting October 2, 1866, and over the next three weeks earned $1,500 which was far more than he had earned from writing.

“The Fortune of My Life”

Aboard the Quaker City, he met fellow passenger Charles Langdon, 18-year-old son of an Elmira, New York coal industry financier. Langdon showed Clemens a little picture of his sister Olivia—friends called her Livy. Clemens was taken by her, and soon after the ship returned to New York, Langdon introduced the two. On New Year’s Eve 1867, Clemens joined Livy and the family to see Charles Dickens read selections from his novels. That evening, Clemens remarked later, referring to Livy, he had discovered “the fortune of my life.”

Then Mark Twain worked on Innocents Abroad, a book full of wry observations about the people he had met and the things he had seen. For example, writing about Morocco: “There is no regular system of taxation, but when the Emperor or the Bashaw want money, they levy on some rich man, and he has to furnish the cash or go to prison. Therefore, few men in Morocco dare to be rich.”

Sam and Livy got married at Quarry Farm, her parents’ Elmira, New York estate, February 2, 1870. She was the only woman he ever loved.

They were an unlikely pair, because she was a strict Victorian. She disapproved of alcohol, tobacco, and vulgar language, vices he was well-known for. He promised only that he wouldn’t smoke more than one cigar at a time. But she loved his tremendous enthusiasm and his refreshingly candid manner. She called him “Youth.”

She became his most trusted editor. She offered her judgment on what kinds of topics readers would be interested in. She read nearly every one of his drafts and suggested changes. She provided advice about his lecture material. “Mrs. Clemens,” he remarked, “has kept a lot of things from getting into print that might have given me a reputation I wouldn’t care to have, and that I wouldn’t have known any better than to have published.”

Roughing It, a witty account of Mark Twain’s travels throughout Nevada and Northern California, buoyed his reputation. In it, among other things, he lavished praise on much-abused Chinese immigrants: they “are quiet, peaceable, tractable, free from drunkedness, and they are as industrious as the day is long . . . . So long as a Chinaman has strength to use his hands he needs no support from anybody . . . . All Chinamen can read, write and cipher with easy facility—pity but all our petted voters could.”

In 1871, the family moved to Hartford, a New England commercial and cultural center about halfway between New York and Boston. They were in Hartford more than 17 years, the period when Mark Twain wrote his most famous books. He collaborated with a neighbor, Charles Dudley Warner, to produce his first fictional work, The Gilded Age. Among his contributions was this shrewd passage about how political power corrupts, which applies as much to the modern welfare state as to government in his own day: “If you are a member of Congress, (no offense,) and one of your constituents who doesn’t know anything, and does not want to go into the bother of learning something, and has no money, and no employment, and can’t earn a living, comes besieging you for help. . . . You throw him on his country. He is his country’s child, let his country support him. There is something good and motherly about Washington, the grand old benevolent Asylum for the Helpless.”

By 1874, Clemens had built an eclectic three-story, 19-room red brick Hartford house which reflected his success and individuality. Part of it looked like the pilot house of a Mississippi steamboat. Clemens spent most of his time there playing billiards and entertaining his daughters Susy, Clara, and Jean (son Langdon had died as an infant). “Father would start a story about the pictures on the wall,” Clara recalled. “Passing from picture to picture, his power of invention led us into countries and among human figures that held us spellbound.”

The family summered at Quarry Farm, and he focused on his books. Apparently, the success of Roughing It suggested that he might do well drawing on other personal experiences, and he pondered his childhood days in Hannibal. His practice was to begin writing after breakfast and continue until dinner—he seldom ate lunch. Evenings, back in the main house, his family gathered around him, and he read aloud what he had written.

In 1875, when he was 40, he started his second novel: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, the poor orphan boy who gets in trouble and redeems himself by being resourceful, honest, and sometimes courageous. There’s a murder, another death, and Tom and his friend Huckleberry Finn fear for their lives, but the book is best-remembered as a charming story of youthful good summer times.

Soon Mark Twain began writing his masterwork, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. He found it hard going, and the book wasn’t published until 1885. Unlike Tom Sawyer, this had the immediacy of a first-person story. In his distinctive colloquial manner, a poor and nearly illiterate 14-year-old son of a town drunkard told how he ran away, and encountered the escaped black slave Jim. Together they floated down the Mississippi River on a raft and got into scrapes. Like many other Southerners, Huck had considered black slaves as sub-human, and he wrote Jim’s owner a letter exposing the runaway. Then he thought about Jim’s humanity. He finally decided he would rather go to hell than betray Jim. He tore up the letter.

Many people considered the book trashy, and it was banned in Concord, Massachusetts. Today, many libraries ban it as racist—the word “nigger” occurs 189 times. But it became a classic for showing real people grappling with the vital issues of humanity and liberty. Huckleberry Finn went on to sell some 20 million copies.

Mark Twain tried public readings of his work, but initial results were a disappointment. “I supposed it would be only necessary to do like Dickens,” he recalled, “get out on the platform and read from the book. I did that and made a botch of it. Written things are not for speech; their form is literary; they are stiff, inflexible and will not lend themselves to happy and effective delivery with the tongue—where their purpose is merely to entertain, not instruct; they have to be limbered up, broken up, colloquialized and turned into the common forms of unpremeditated talk—otherwise they will bore the house, not entertain it. After a week’s experience with the book I laid it aside and never carried it to the platform again; but meantime I had memorized those pieces, and in delivering them from the platform they soon transformed themselves into flexible talk, with all their obstructing preciseness and formalities gone out of them for good.” As a lecturer, he became an international sensation.

Financial Failure

Clemens should have enjoyed financial peace of mind, but he invested his earnings as well as his wife’s inheritance on inventions and other business ventures which never panned out. His investment in a new kind of typesetter turned into a $190,000 loss. Incredibly, he failed as the publisher of his own immensely popular books. In 1894, his publishing firm went bankrupt with $94,000 of debts owed to 96 creditors. Clemens was 59, and few people bounced back at that age.

He assumed personal responsibility for the mess instead of ducking behind limited liability laws. He got invaluable help from a fan, John D. Rockefeller partner Henry Rogers, who managed the author’s financial affairs. Clemens resolved to repay his creditors by generating more lecture income. He, his wife, Livy, and daughter Clara boarded a train and began a grueling cross-country tour. Lecture halls were packed. Then the family traveled to Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, India, South Africa, and England, and everywhere he played to cheering crowds. “We lectured and robbed and raided for thirteen months,” he recalled. By January 1898, he was debt-free.

Mark Twain hailed individual enterprise and spoke out against injustice wherever he found it. He persuaded Rogers to help provide money so that Helen Keller could get an education commensurate with her extraordinary ability. At Carnegie Hall, Mark Twain presided at a large gathering to support Booker T. Washington and self-help among blacks. While Mark Twain was living in Vienna (1897-1900), he defied the virulent anti-Semitic press and defended French Captain Alfred Dreyfus whom French military courts had convicted of treason because he was Jewish.

Meanwhile, Clemens suffered family tragedies. While he was lecturing in England, on August 18, 1894, his daughter Susy died of meningitis. His wife Livy, partner for 34 years, succumbed to a heart condition June 5, 1904. “During those years after my wife’s death,” he recalled, “I was washing about on a forlorn sea of banquets and speech-making in high and holy causes, and these things furnished me intellectual cheer and entertainment; but they got at my heart for an evening only, then left it dry and dusty.”

Many critics have dismissed Mark Twain’s writings from the last decade of his life as the work of a man embittered by too many tragedies. In this period, he significantly increased his output of political commentary. He attacked fashionable collectivist doctrines of “progressive” thinkers who called for more laws, bureaucrats and military adventures.

Like Lord Acton, Mark Twain demanded that the government class be held to the same moral standard as private individuals. “Our Congresses consist of Christians,” he wrote in his little-known work Christian Science (1907). “In their private life they are true to every obligation of honor; yet in every session they violate them all, and do it without shame; because honor to party is above honor to themselves. In private life those men would bitterly resent—and justly—any insinuation that it would not be safe to leave unwatched money within their reach; yet you could not wound their feelings by reminding them that every time they vote ten dollars to the pension appropriation nine of it is stolen money and they the marauders.”

Mark Twain made his anti-imperialist views clear at Manhattan’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel when he introduced Winston S. Churchill, the future English statesman who was about to regale Americans with his Boer War exploits. “I think that England sinned in getting into a war in South Africa which she could have avoided without loss of credit or dignity,” Mark Twain declared, “just as I think we have sinned in crowding ourselves into a war in the Philippines on the same terms.” Mark Twain’s satirical “War Prayer” became an anthem for those who wanted to keep America out of foreign wars.

After the death of his daughter Jean in December 1909, the result of an epileptic seizure, Clemens tried to revive his spirits in Bermuda. But angina attacks, which had occurred during the previous year, intensified and became more frequent. Doctors administered morphine to relieve the pain. He boarded a ship for his final trip home. Clemens died at Stormfield, his Redding, Connecticut, house, on Thursday morning, April 21, 1910. Thousands of mourners took a last look at him, decked out in his white suit, at Brick Presbyterian Church, New York City. He was buried beside his wife in Elmira, New York.

By then, he was quite out of tune with his times. “Progressives” and Marxists certainly didn’t like his brand of individualism. The public lost interest. Mark Twain’s daughter Clara and his authorized biographer Albert Bigelow Paine blocked access to the author’s papers. Beside Mark Twain’s intimates, about the only defense came from individualist literary critic H.L. Mencken: “I believe that he was the true father of our national literature, the first genuinely American artist of the blood royal.”

The situation gradually began to change. In 1962 respected University of Chicago English professor Walter Blair wrote Mark Twain and Huck Finn, which treated the author’s Mississippi River epic as major-league literature. Before Blair’s book, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn rarely appeared in a college curriculum—American literature got little respect. Now Huck Finn is taught almost everywhere.

Also in 1962, Clara Clemens Samossaud died. Her Mark Twain papers—letters, speeches, original manuscripts, and unpublished works—became the property of the University of California (Berkeley). It encouraged writers to work with the material, and since then dozens of new books about Mark Twain have appeared. Moreover, Berkeley Mark Twain editors launched an ambitious scholarly project to publish everything he wrote, including papers held by other institutions and private individuals. Mark Twain Project head Robert Hirst estimates the papers could eventually fill 75 robust volumes.

Mark Twain has been raked over by the politically correct crowd, but he endures as the most beloved champion of American individualism. Unlike so many of his contemporaries, he didn’t believe America was a European outpost. He cherished America as a distinct civilization. He defended liberty and justice indivisible. He promoted peace. He portrayed rugged, resourceful free spirits who overcome daunting obstacles to fulfill their destiny. His personal charm and wicked wit still make people smile.

Jim Powell

Jim Powell, senior fellow at the Cato Institute, is an expert in the history of liberty. He has lectured in England, Germany, Japan, Argentina and Brazil as well as at Harvard, Stanford and other universities across the United States. He has written for the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Esquire, Audacity/American Heritage and other publications, and is author of six books.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment