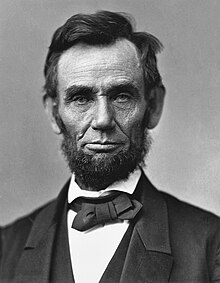

This Day in History: Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States on this day in 1860.

Did you know that both President and Mrs. Lincoln were superstitious.

From William Eleazar Barton 1920:

They believed in dreams and signs, he more in dreams and she more in signs. When Mrs. Lincoln was away from him for a little time, visiting in Philadelphia in 1863, and Tad with her, Lincoln thought it sufficiently important to telegraph, lest the mail should be too slow, and sent her this message:

"Executive Mansion,

"Washington, June 9, 1863.

"Mrs. Lincoln,

"Philadelphia, Pa.

"Think you better put Tad's pistol away. I had an ugly dream about him. "A. Lincoln"

—Quoted in facsimile in Harper's Magazine for February, 1897; Lincoln's Home Life in the White House, by Leslie J. Perry.

In Lamon's book of Recollections, published in 1895, a very different book from his Life of Lincoln, he devotes an entire chapter to Lincoln's dreams and presentiments. He relates the story of the dream which Lincoln had not long before his assassination wherein he saw the East Room of the White House containing a catafalque with the body of an assassinated man lying upon it. Lincoln tried to remove himself from the shadow of this dream by recalling a story of life in Indiana, but could not shake off the gloom of it. Lamon says:

"He was no dabbler in divination, astrology, horoscopy, prophecy, ghostly lore, or witcheries of any sort. . . . The moving power of dreams and visions of an extraordinary character he ascribed, as did the Patriarchs of old, to the Almighty Intelligence that governs the universe, their processes conforming strictly to natural laws."—Recollections, p. 120.

In his Life of Lincoln, Lamon tells the story of the dream which Lincoln had late in the year 1860, when resting upon a lounge in his chamber he saw his figure reflected in a mirror opposite with two images, one of them a little paler than the other. It worried Lincoln, and he told his wife about it. She thought it was "a sign that Lincoln was to be elected for a second term and that the paleness of one of the faces indicated that he would not see life through the last term" (p. 477).

As this optical illusion has been so often printed, and has seemed so weirdly prophetic of the event which followed, it may be well to quote an explanation of the incident from an address by Dr. Erastus Eugene Holt, of Portland, Maine:

"As he lay there upon the couch, every muscle became relaxed as never before. ... In this relaxed condition, in a pensive mood and in an effort to recuperate the energies of a wearied mind, his eyes fell upon the mirror in which he could see himself at full length, reclining upon the couch. All the muscles that direct, control, and keep the two eyes together were relaxed; the eyes were allowed to separate, and each eye saw a separate and distinct image by itself. The relaxation was so complete, for the time being, that the two eyes were not brought together, as is usual by the action of converging muscles, hence the counterfeit presentiment of himself. He would have seen two images of anything else had he looked for them, but he was so startled by the ghostly appearance that he felt 'a little pang as though something uncomfortable had happened,' and obtained but little rest. What a solace to his wearied mind it would have been if someone could have explained this illusion upon rational grounds!" —Address at Portland, Maine, February 12, 1901, reprinted by William Abbatt, Tarrytown, N. Y., 1916.

Other incidents which relate to Mr. Lincoln's faith in dreams, including one that is said to have occurred on the night preceding his assassination, are well known, and need not be repeated here in detail.

It is not worth while to seek to evade or minimize the element of superstition in Lincoln's life, nor to ask to explain away any part of it. Dr. Johnson admits it in general terms, but makes little of concrete instances:

"The claim that there was more or less of superstition in his nature, and that he was greatly affected by his dreams, is not to be disputed. Many devout Christians today are equally superstitious, and, also, are greatly affected by their dreams. Lincoln grew in an atmosphere saturated with all kinds of superstitious beliefs. It is not strange that some of it should cling to him all his life, just as it was with Garfield, Blaine, and others.

"In 1831, then a young man of twenty-two, Lincoln made his second trip to New Orleans. It was then that he visited a Voodoo fortune teller, that is so important in the eyes of certain people. This, doubtless, was out of mere curiosity, for it was his second visit to a city. This no more indicates a belief in 'spiritualism' than does the fact that a few days before he started on this trip he attended an exhibition given by a traveling juggler, and allowed the magician to cook eggs in his low-crowned, broad-rimmed hat."—Lincoln the Christian, p. 29.

I do not agree with this. Superstition was inherent in the life of the backwoods, and Lincoln had his full share of it. Superstition is very tenacious, and people who think that they have outgrown it nearly all possess it. "I was always superstitious," wrote Lincoln to Joshua F. Speed on July 4, 1842. He never ceased to be superstitious.

While superstition had its part in the life and thought of Lincoln, it was not the most outstanding fact in his thinking or his character. For the most part his thinking was rational and well ordered, but it had in it many elements and some strange survivals—strange until we recognize the many moods of the man and the various conditions of his life and thought in which from time to time he lived.

They believed in dreams and signs, he more in dreams and she more in signs. When Mrs. Lincoln was away from him for a little time, visiting in Philadelphia in 1863, and Tad with her, Lincoln thought it sufficiently important to telegraph, lest the mail should be too slow, and sent her this message:

"Executive Mansion,

"Washington, June 9, 1863.

"Mrs. Lincoln,

"Philadelphia, Pa.

"Think you better put Tad's pistol away. I had an ugly dream about him. "A. Lincoln"

—Quoted in facsimile in Harper's Magazine for February, 1897; Lincoln's Home Life in the White House, by Leslie J. Perry.

In Lamon's book of Recollections, published in 1895, a very different book from his Life of Lincoln, he devotes an entire chapter to Lincoln's dreams and presentiments. He relates the story of the dream which Lincoln had not long before his assassination wherein he saw the East Room of the White House containing a catafalque with the body of an assassinated man lying upon it. Lincoln tried to remove himself from the shadow of this dream by recalling a story of life in Indiana, but could not shake off the gloom of it. Lamon says:

"He was no dabbler in divination, astrology, horoscopy, prophecy, ghostly lore, or witcheries of any sort. . . . The moving power of dreams and visions of an extraordinary character he ascribed, as did the Patriarchs of old, to the Almighty Intelligence that governs the universe, their processes conforming strictly to natural laws."—Recollections, p. 120.

In his Life of Lincoln, Lamon tells the story of the dream which Lincoln had late in the year 1860, when resting upon a lounge in his chamber he saw his figure reflected in a mirror opposite with two images, one of them a little paler than the other. It worried Lincoln, and he told his wife about it. She thought it was "a sign that Lincoln was to be elected for a second term and that the paleness of one of the faces indicated that he would not see life through the last term" (p. 477).

As this optical illusion has been so often printed, and has seemed so weirdly prophetic of the event which followed, it may be well to quote an explanation of the incident from an address by Dr. Erastus Eugene Holt, of Portland, Maine:

"As he lay there upon the couch, every muscle became relaxed as never before. ... In this relaxed condition, in a pensive mood and in an effort to recuperate the energies of a wearied mind, his eyes fell upon the mirror in which he could see himself at full length, reclining upon the couch. All the muscles that direct, control, and keep the two eyes together were relaxed; the eyes were allowed to separate, and each eye saw a separate and distinct image by itself. The relaxation was so complete, for the time being, that the two eyes were not brought together, as is usual by the action of converging muscles, hence the counterfeit presentiment of himself. He would have seen two images of anything else had he looked for them, but he was so startled by the ghostly appearance that he felt 'a little pang as though something uncomfortable had happened,' and obtained but little rest. What a solace to his wearied mind it would have been if someone could have explained this illusion upon rational grounds!" —Address at Portland, Maine, February 12, 1901, reprinted by William Abbatt, Tarrytown, N. Y., 1916.

Other incidents which relate to Mr. Lincoln's faith in dreams, including one that is said to have occurred on the night preceding his assassination, are well known, and need not be repeated here in detail.

It is not worth while to seek to evade or minimize the element of superstition in Lincoln's life, nor to ask to explain away any part of it. Dr. Johnson admits it in general terms, but makes little of concrete instances:

"The claim that there was more or less of superstition in his nature, and that he was greatly affected by his dreams, is not to be disputed. Many devout Christians today are equally superstitious, and, also, are greatly affected by their dreams. Lincoln grew in an atmosphere saturated with all kinds of superstitious beliefs. It is not strange that some of it should cling to him all his life, just as it was with Garfield, Blaine, and others.

"In 1831, then a young man of twenty-two, Lincoln made his second trip to New Orleans. It was then that he visited a Voodoo fortune teller, that is so important in the eyes of certain people. This, doubtless, was out of mere curiosity, for it was his second visit to a city. This no more indicates a belief in 'spiritualism' than does the fact that a few days before he started on this trip he attended an exhibition given by a traveling juggler, and allowed the magician to cook eggs in his low-crowned, broad-rimmed hat."—Lincoln the Christian, p. 29.

I do not agree with this. Superstition was inherent in the life of the backwoods, and Lincoln had his full share of it. Superstition is very tenacious, and people who think that they have outgrown it nearly all possess it. "I was always superstitious," wrote Lincoln to Joshua F. Speed on July 4, 1842. He never ceased to be superstitious.

While superstition had its part in the life and thought of Lincoln, it was not the most outstanding fact in his thinking or his character. For the most part his thinking was rational and well ordered, but it had in it many elements and some strange survivals—strange until we recognize the many moods of the man and the various conditions of his life and thought in which from time to time he lived.

See also Killing Abraham Lincoln - 40 Books on CDrom (Plus Garfield & McKinley) and The Dark Side of Abraham Lincoln - Over 50 Books on CDROM and 220 Books on the American Civil War on DVDrom 1861-1865

For a list of all of my disks and ebooks (PDF and Amazon) click here

For a list of all of my disks and ebooks (PDF and Amazon) click here

No comments:

Post a Comment