The Two Babylons; on The Papal Worship Proved To Be The Worship Of Nimrod And His Wife By The Rev. Alex. Hislop, of East Free Church, Arbroath

Review in The Evangelical Witness and Presbyterian Review 1865

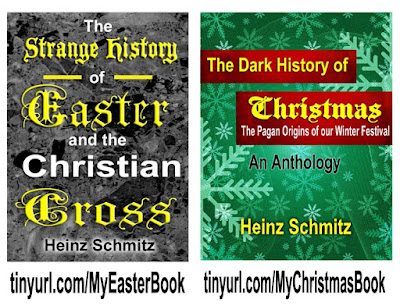

Book available at The Mystery Religions and Ancient Gods, 200 Books on DVDrom and Over 250 Books on DVDrom on Mythology, Gods and Legends

Some years ago, a pamphlet with the foregoing title created much interest among those who trace the family resemblance among religious systems of more or less corrupted form. The argument of that pamphlet issued by Mr. Drummond, of Stirling, is here re-produced with a mass of evidence and illustration which only learning, research, patient inquiry, and considerable outlay of means could have brought together. The illustrations from Nineveh, Babylon, Egypt, and Pompeii, with which the books of curious travellers have made us familiar, are here in a new setting, and form part of a most ingenious, and indeed startling inquiry. The author acknowledges obligation to Lord John Scott and an Irish M.P. whose name does not transpire, and to well-known authors and publishers who have given the use of materials they had collected. Indeed, on no other principle than that of combined labour can we conceive of a volume such as this being produced by a minister living in the quiet of a country town, and amid the duties of a pastorate. Any one who looks at the formidable list of works quoted— occupying half-a-dozen pages—will set down the volume as dull and hard reading, but this impression vanishes on further examination. To find "Hogmanay" identified with the worship of the moon, and the Christmas-day her supposed birth-day—to find Jerome in connection therewith describing the usages on this day in Egypt, and at Alexandria, usages that (substituting whiskey for wine) prevail in Scotland still, is something surprising. Our Christmas tree was equally common in Pagan Rome and Pagan Egypt. The yule-log is put into the fire on Christmas eve, and the Christmas tree comes out the next morning — the re-production of Nimrod deified as the sun god, cut down by his enemies, but revived again. "Kissing under the misletoe" is connected with a Babylonish symbol, to which Mr. Hislop supposes Psalm lxxxv. 10, 11 may allude, the people of Israel having been brought into contact with Babylon. The boar's head is similarly traced from the worship of Tammuz or Adonis downward to the English Christmas festival. The worship of Osiris by an offering of a goose, has been fatal to this bird in many a Christian land at the corresponding season. These historical curiosities are parts of the evidence that "Lady-day and Christmas day are purely Babylonian."

So Easter is Astarte, one of the titles of the queen of heaven, found as Ishtar by Layard at Babylon. "The hot cross buns" and the coloured eggs figured in this Chaldean worship as they do on "Good Friday" and Easter Sunday. "Now the Romish Church adopted this mystic egg of Astarte and consecrated it as a symbol of Christ's resurrection," Paul V. having appointed a form of prayer, "Bless O Lord, .... this Thy creature of eggs, that it may become a wholesome sustenance unto thy servants, eating it in remembrance of our Lord Jesus Christ."

But it is impossible to condense the researches of this most fascinating book; suffice it to say that Lent, the sign of the cross, celibacy, clothing and crowning of images, relic-worship, the bonfires of St. John's eve, the priestly celibacy of Thibet, China, Japan, and Rome, the clerical tonsure, and many other peculiarities, are traced with wonderful clearness through classical and patristic authors, through Roman and Druidical rites, till they were adopted by "the Church" which absorbed the nations, by accepting and consecrating their heathenism. To the antiquarian, the controversialist, the Christian, and to the mere philosopher who examines with interest the strange currents of thought and feeling that run through the race and prove its unity, this book is full of attractions. We regret that it is little known in Ireland, and we commend it to the attention of the thoughtful.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Review from The British and Foreign Evangelical Review 1865

Before closing our paper, we may briefly notice another recent work of much ability, in which great ingenuity and research have been brought to bear upon the subject before us. It is entitled "The Two Babylons," and is written by the Rev. Alexander Hislop, Minister of the East Free Church, Arbroath. The author points out that, so early as A.D. 230, Tertullian deeply lamented the tendency of many of the Christian disciples to meet paganism half way; and he shows in what a variety of instances the Church of Rome has sanctioned and adopted purely pagan beliefs and practices which have no warrant from the Bible, and are often directly opposed both to its letter and spirit. Some of these, not already touched upon, we shall now very shortly notice. Mr. Hislop affirms that there are strong reasons for believing that the Madonna, enshrined in the sanctuaries of Romanism, is the very Queen of Heaven, for the worship of whom the fierce anger of God was kindled against the Jews in the days of Jeremiah. He also points out that the mass is a ceremony of pagan origin. In ancient times the altars of the Assyrian and Cyprian Venus were carefully kept from blood, an "unbloody sacrifice" was offered to them by their worshippers, and the Assyrian Venus bore at Babylon the name of "Mulitta," or "Mediatrix." The wafer in the sacrifice of the mass was first used by the women of Arabia, and on its introduction all true Christians at once perceived its real character and its pagan origin. Those who adopted it were at first treated as heretics, and branded with the name of Collyridians, from the Greek word for the "cake," which they employed. But Rome soon perceived that this heresy might be turned to good account; and therefore, though condemned by the sound portion of the Church, the practice of offering and eating this unbloody sacrifice was encouraged by the Papacy, until, throughout the wide limits of the Romish communion, it had superseded the simple and precious Sacrament of the Supper, as instituted by our Lord himself.

Like the mass, extreme unction is stated by Mr. Hislop to be of pagan origin. In the pagan rites, unction played a very important part. Those who came to consult the oracle of Trophonius were rubbed with oil over the whole body, a process which probably tended to excite the imagination and produce the desired vision, as stimulating drugs might in this way easily be introduced into the system. Apollonius and his companions, before being admitted into the mysteries of the Indian sages, were rubbed over with an oil so powerful that they felt as if bathed with fire. This was professedly an unction, in the name of the "Lord of Heaven," to fit and prepare them for being admitted, in vision, into his awful presence. The very same reason that suggested such an unction before initiation, while still on this side the tomb, would naturally plead still more powerfully for a special unction, when the individual was about to be called, not in vision, but in reality, to face the mystery of mysteries—his personal introduction into the unseen and eternal world. Thus the pagan rite was gradually developed into the Popish ceremony of extreme unction—a ceremony entirely unknown among Christians until corruption had made great advances in the Church. Bishop Gibson (Preservative against Popery) says that it was not known for 1,000 years after Christ.

Mr. Hislop tells us that in every religious system, except that of the Bible, the doctrine of purgatory and prayers for the dead will be found to occupy a place. It formed a part of the religious system of Egypt; in Greece it was inculcated by Plato in the Phaedrus, and by several other famous philosophers; in pagan Rome also, the same doctrine was taught, and Virgil describes the torments of purgatory in the Sixth Book of the Aeneid. In heathen, as in Roman Catholic countries, prayers for the dead formed a great source of wealth to the priesthood, who well knew how to take advantage of the sensitive tenderness of relations for the happiness of the beloved dead. In India, Egypt, Tartary, Greece, and Rome, various competent observers have borne testimony to the costliness of these posthumous devotions, which appear to have been as burdensome to the relatives, and as lucrative for the priesthood, in ancient as in modern times. In the pagan purgatory, as depicted by Virgil, fire, water, and winds are represented as combining to purge away the stains of sin; in the Papal purgatory fire alone is always represented as the grand means of purgation.

We have already pointed out how completely the adoration of the relics of saints and martyrs is a practice borrowed from paganism, and we refer those who would wish to examine the subject more minutely to the pages of Mr. Hislop, where they will find it thoroughly investigated. We proceed to notice his observations with regard to the pagan origin of the rosary and the sign of the cross. The rosary was commonly employed by the Brahmins, and is mentioned in the sacred books of the Hindus. It was also used in Asiatic Greece and in pagan Rome; and Sir John F. Davis thus describes its appearance and use in China: "From the Tartar religion of the Lamas, the rosary of 108 beads has become a part of the ceremonial dress attached to the nine grades of official rank. It consists of a necklace of stones and coral, nearly as large as a pigeon's egg, descending to the waist, and distinguished by various beads, according to the quality of the wearer. There is a small rosary of beads of inferior size, with which the bonzes count their prayers and ejaculations, exactly as in the Romish ritual. Every one is familiar with the importance of the sign and image of the cross in the Romish system; how it is adored with the homage due only to God, and how all kinds of magic virtues are attributed to it. Mr. Hislop, however, tells us that the same sign of the cross which Rome now worships was used in the Babylonian mysteries, was applied to the same magic purposes, and was honoured with the same honours. The cross was not originally a Christian emblem, but was the mystic Tau of the Chaldeans and Egyptians—the true original form of the letter T. This mystic sign was marked in baptism on the foreheads of those who were initiated into the mysteries, and was used in a variety of other ways as a sacred symbol. It was worn as an amulet over the heart, was marked on the official garments of the pagan priesthood as on those of the Romish priests, and was borne by kings in their hands as a token of dignity or divinely-conferred authority. The vestal virgins of Rome had it suspended from their necklaces, just as the nuns now wear it. It was in use as early as the fifteenth century belore the Christian era. The heathen Celts worshipped it, and it was a favourite emblem among the Buddhists. This pagan symbol was first adopted by the Christians of Egypt, and Sir G. Wilkinson says of it: "A still more curious fact may be mentioned respecting this hieroglyphical character (the Tau), that the early Christians of Egypt adopted it in lieu of the cross which was afterwards substituted for it, prefixing it to inscriptions in the same manner as the cross in later times. For, though Dr. Young had some scruples in believing the statement of Sir A. Edmonstone. that it holds that position in the sepulchres of the Great Oasis, I can attest that such is the case, and that numerous inscriptions headed by the Tau are preserved to the present day as early Christian monuments." From all this Mr. Hislop argues that the earliest form of what has since been called the cross was no other than the crux ansata, or sign of life, borne by Osiris and all the Egyptian gods. The handle, or ansa, was afterwards dispensed with, when it became the simple Tau, or ordinary cross, as it appears at the present day. But it is clear that its first employment on the sepulchres could have no reference to the crucifixion of our Lord, but was simply the result of attachment to old and long-cherished Pagan symbols.

In following out inquiries of this sort, there is considerable risk that the inquirer should be led on too far—that he should mistake a remote or accidental analogy for a close and perfect resemblance; and we are inclined to think that, with all his learning, research, and perfect good faith, Mr. Hislop has occasionally fallen into this error. He has, however, been thoroughly successful in the main object of his work—the demonstration that the religion of Rome is in reality but baptized paganism, disguised by a thin veil of Christianity. Y.

No comments:

Post a Comment