Wednesday, May 31, 2023

Walter Sickert (the Ripper?) on This Day in History

Tuesday, May 30, 2023

TaB Cola on this Day in History

Monday, May 29, 2023

Doomsayer Paul Ehrlich on This Day in History

CBS recently featured infamous doomsayer Paul Ehrlich on their long-running show 60 Minutes. In his segment, Ehrlich tries to convince viewers we’re on a fast track to an environmental disaster of existential proportions, particularly when it comes to animal extinctions.

"In ten years all important animal life in the sea will be extinct,” Ehrlich said. “Large areas of coastline will have to be evacuated because of the stench of dead fish."

But that quote isn’t from the 60 Minutes appearance.

The problem is he said that back in 1970. And he’s saying the exact same thing in the year of our Lord 2023.

Ehrlich has been singing this same song for nearly 60 years. In his 1968 book, The Population Bomb, Ehrlich announced to the world that the 21st century would be one of poverty and mass starvation brought about by overpopulation.

He famously claimed that England would no longer exist in the year 2000 because of environmental disasters caused by overpopulation, and his biggest claim to fame is losing a bet to the late economist Julian Simon about the increasing abundance of resources.

On Twitter, Ehrlich is unhappy that people are ignoring his awards and homing in on his stupendous mistakes.

The last line of his Tweet, that he’s made no basic mistakes, is wrong as well. We know this is true, because Ehrlich always makes mistakes that go in the same direction. He always over-predicts environmental crises and never under-predicts them.

This systematic error is indicative of a basic error. For example, if you always show up five minutes late to everything despite an intention to show up on time, it must be the case that you are making some basic mistake. Maybe your clock is 5 minutes slow, maybe you’ve underestimated your commute, or maybe you take longer to get ready than you think. It’s not just random chance because if it were random you’d also be 5 minutes early sometimes.

Similarly, Ehrlich has made the most basic mistake of all, which is at the root of all his other mistakes.

Ignoring Ingenuity

I’m not going to go through the details of Ehrlich being wrong about extinction woes here, because other articles have successfully highlighted how peer-reviewed research acknowledges the failure of the sorts of estimates Ehrlich relies on.

Another thing that works against Ehrlich is, again, he’s made these same claims before and they didn’t bear out.

But the biggest issue with Ehrlich is that he does make a basic mistake—one that Julian Simon tried to explain to him for many years.

Ehrlich sees humans as mouths to feed in a literal and metaphorical sense. To Ehrlich, humans are consumers, not much different than the animal populations he’s used to studying.

But humans are different in that they can use their creative capacity to reshape and create their environments to their liking in unparalleled ways. In Simon’s words, “Human beings are not just more mouths to feed, but are productive and inventive minds.”

The earliest incarnation of Ehrlich’s concerns about the environment were that we would run out of food, land, and other natural resources.

But to paraphrase Simon, resources come out of the human mind—not the ground. Consider oil. What causes us to treat oil as a valuable commodity worthy of our pursuit rather than some gross black liquid? Human ingenuity.

The ability to convert the black liquid into things like heat, transportation, and food distribution for millions of people was created via humans.

And humans can increase the supply of supposedly fixed resources through innovation. Doubling the fuel efficiency of cars effectively doubles the amount of oil available for driving. We also develop new techniques for extracting previously unattainable oil. These sort of processes are why Ehrlich and many scientists over the years have tried and failed to predict “peak oil” estimates.

Ehrlich frequently blames the Green Revolution in agriculture for confounding his predictions about mass starvation. The problem? The Green Revolution was the result of the very human minds Ehrlich was blaming for the ongoing disaster. A smaller population means fewer minds to produce new ideas, and less demand to compensate individuals for those ideas.

Because Ehrlich consistently focuses on the cost human beings bring to the table but never the benefit, he is systematically incorrect in his predictions.The fact that Ehrlich constantly overpredicts disaster and never underpredicts it is evidence of this basic systematic error.

In response to his failures, Ehrlich has said it’s unlikely that another innovation like the Green Revolution can occur. But why? Ehrlich failed to predict the first Green Revolution, so why would we expect he would be able to predict a second massive innovation?

At this point readers may argue that Ehrlich’s most recent interview is a different type of issue. In the past he was wrong about the abundance of resources, but now he’s talking about species extinctions. How can human ingenuity solve that?

Human creativity is not limited to simple commodities. Anything that humans value can be protected and sustained through creative ways.

One claim made by those concerned about extinctions is that eliminating biodiversity will destroy, for example, molds, fungi, and other organisms beneficial for humans. Penicillin is a primary example of a mold of this type. Imagine if there was an organism which could do as much good for humans as Penicillin but went extinct before we discovered it.

But humans are now on the cusp of being able to create these sorts of organisms ourselves. Gene editing research and technology has put scientists in the position of essentially creating new organisms which could fulfill the role of a theoretically extinct mold. Innovation outpaces destruction.

Other concerns involve consideration for animals who may become extinct. Concerns for these animals are expressed both because of the benefit they bring to humans (think bees) or for their own sake (rhinos).

Are humans powerless to use innovation to stop these problems? Again, no.

The Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) illustrates this well with the story of white rhinos. In 1900, only about 20 white rhinos remained on earth. The few that remained existed in a game reserve.

But in 1991, something changed. PERC explains:

“Before 1991, all wildlife in South Africa was treated by law as res nullius or un-owned property. To reap the benefits of ownership from a wild animal, it had to be killed, captured, or domesticated. This created an incentive to harvest, not protect, valuable wild species—meaning that even if a game rancher paid for a rhino, the rancher could not claim compensation if the rhino left his property or was killed by a poacher.”

Starting in 1991, ownership of white rhinos has been legally upheld. As a result, white rhino populations have soared. There are close to 20,000 white rhinos today with a general increase in population over the last 20 years.

On the other hand, black rhinos—which live primarily in countries with weaker environmental property rights institutions—have declined in population from 100,000 to around 6,000 today.

Giving someone the right to own animals and sell them provides an incentive to protect against poachers and overexploitation. Ranchers systematically slaughter cattle for money, but we don’t have any concern about cow extinction because market incentives encourage private individuals to maintain the populations for the future.

Human ingenuity, given the proper institutions which protect property and liberty, will continue to win out over environmental catastrophe.

Until Ehrlich understands that human creativity is a fundamentally different topic of study from his own, his basic mistake will continue to produce the sorts of mistakes which earned Julian Simon $576.07 against him.

Doomsaying Has Consequences

If no one listened to Ehrlich’s doomsaying, this could be just a funny joke. Sadly, Paul Ehrlich isn’t just bad at forecasting the future. Ehrlich explicitly advocated for the use of forms of coercion if necessary to curb the population “problem” in his 1968 book. In his chapter “What Needs to Be Done?” Ehrlich said,

“A good example of how we might have acted can be built around the [Dr.] Chandrasekhar incident I mentioned earlier. When we suggested sterilizing all Indian males with three or more children, he should have encouraged the Indian government to go ahead with the plan. We [the United States] should have volunteered logistic support in the form of helicopters, vehicles, and surgical instruments. We should have sent doctors to aid in the program by setting up centers for training para-medical personnel to do vasectomies. Coercion? Perhaps, but coercion in a good cause (emphasis added).”

This is tyrannical.

Unfortunately, many countries listened to rhetoric similar to Ehrlich’s. In the 1970s China began its one child policy which is responsible for countless forced sterilizations and abortions. The architect of China’s policy utilized work from The Club of Rome, an anti-population think tank and intellectual fellow-travelers of Ehrlich.

Note, I’m not saying Ehrlich created these policies (though he may have liked to based on his comments), but being one of the loudest intellectuals stoking fears of overpopulation and calling for coercion in an era where some of the biggest human rights violations of this kind occurred certainly merit him some culpability.

The same anti-population pandemonium led to the establishment of the United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA) Award which was awarded to the coercive population programs of China and India.

The echoes of this sort of policy even persist into recent times. As recently as the 1990s, the Peruvian government facilitated its own coercive sterilization program.

So these ideas aren’t just wrong. They are actively harmful when applied. But we don’t have to let them be. Opponents of anti-human ideas can pick up where Julian Simon left off and improve the intellectual conversation by combatting doomsayers.

I encourage interested readers to check out the recent symposium on Julian Simon I co-edited with professor Louis Rouanet in the Review of Austrian economics. The pieces in the issue show Simon’s research program is alive and well.

For readers more interested in books, I recommend Superabundance by Gale Pooley and Marian Tupy as well as their work on the Simon Project.

And Simon’s original magnum opus, The Ultimate Resource, holds up well today and is available for free (albeit in not-so-reader-friendly form) on his website.

Julian Simon’s ultimate claim was that human innovation would cause material conditions to continue to improve so long as freedom and private property were preserved. It’s not clear that academic ideas will also follow this trend, but it doesn’t seem unreasonable to think so.

I certainly hope ideas and discourse will continue to improve, and, if so, we may one day reach a future where Ehrlich’s ideas are extinct from reasonable minds and powerful institutions.

Peter Jacobsen

Peter Jacobsen teaches economics and holds the position of Gwartney Professor of Economics. He received his graduate education at George Mason University.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

Sunday, May 28, 2023

The Paris Commune on This Day in History

Saturday, May 27, 2023

Christopher Lee on This Day in History

Friday, May 26, 2023

Serial Killer Anthony Joyner on This Day in History

Thursday, May 25, 2023

The Gateway Arch on This Day in History

Wednesday, May 24, 2023

The Sale of Manhattan on This Day in History

Tuesday, May 23, 2023

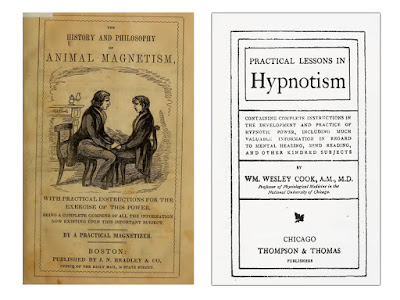

Franz Mesmer on This Day in History

Monday, May 22, 2023

LBJ's Great Society on This Day in History

This Day in History: U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson launched his Great Society program on this day in 1964.

From Robert Higgs:

For the most part President Lyndon B. Johnson was simply lucky in regard to economic stability and growth during his term in office, although he does deserve credit for pushing John F. Kennedy’s stalled tax-cut proposal to quick enactment in February 1964. The economy was already growing and the rate of unemployment declining when LBJ took office in November 1963, and macroeconomic conditions continued to improve throughout his presidency, although the rate of inflation began to edge up after 1965, reaching almost 5 percent during his final year in office. Between 1963 and 1968 real gross domestic product increased 29 percent, or 5.2 percent per year on average. Unemployment declined from 5.7 percent in November 1963, when LBJ became president, to 3.4 percent in January 1969, when he left office.

This macroeconomic success owed nothing to policymakers’ fine tuning, because neither the administration nor Congress made such delicate adjustments of fiscal policy as conditions changed. In truth, the U.S. government was institutionally incapable of fine tuning fiscal policy, however much it appealed to Keynesian economists drawing diagrams on blackboards.

Whatever its sources, this remarkable macroeconomic performance deserves the lion’s share of the credit for the reduction in measured poverty that occurred during the Great Society years. Of course the administration did propose, gain enactment of, and implement a plethora of bills aimed at reducing poverty in one way or another. Indeed, for many observers, the Great Society is virtually synonymous with the War on Poverty.

Major events included enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (often viewed as an antipoverty measure because blacks had relatively low average income), the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, the Food Stamp Act of 1964, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, and the Social Security Amendments of 1965 (creating Medicare and Medicaid), as well as establishment of the Office of Economic Opportunity (to oversee programs such as VISTA, Job Corps, Community Action Program, and Head Start), hundreds of Community Action Agencies, and many other bureaus ostensibly promoting poor people’s health, education, job training, and welfare.

Nearly all these antipoverty measures, if successful at all, had only a small effect on the national poverty rate, which fell from 19.5 percent in 1963 to 12.8 percent in 1968. Many of the antipoverty programs had scant funding and received news coverage out of proportion to the amount of money they spent. Most of the programs were ineffectual, spending taxpayer money with little or nothing to show for their display of good intentions. “[T]hose who most directly benefited,” says historian Allen J. Matusow, “were the middle-class doctors, teachers, social workers, builders, and bankers who provided federally subsidized goods and services of sometimes suspect value.”

Poverty researcher Michael D. Tanner recently remarked, apropos of the War on Poverty and its programmatic legacies:

Throwing money at the problem has neither reduced poverty nor made the poor self-sufficient. Instead, government programs have torn at the social fabric of the country and been a significant factor in increasing out-of-wedlock births with all of their attendant problems. They have weakened the work ethic and contributed to rising crime rates. Most tragically of all, the pathologies they engender have been passed on from parent to child, from generation to generation.

The Great Society at least did not bring economic growth to a halt, and therefore did not preclude a continuation of the long-term reduction in the proportion of Americans living in poverty. As for the War on Poverty in particular, however, no such benign evaluation is justified. Matusow, by no means a conservative ideologue, concludes that “the War on Poverty was destined to be one of the great failures of twentieth-century liberalism.”

Like most of the other Great Society programs, the War on Poverty rested on the presumption that technocrats possessed the knowledge and capacity to identify what needed to be done, design appropriate remedial measures, and implement those measures successfully through the use of government’s coercive power and taxpayers’ money. The technocrats did not give much weight—indeed, they generally gave no weight whatsoever—to the possibility of what later came to be known in Public Choice theory as “government failure.”

According to LBJ’s biographer, Paul Conkin, Johnson “never easily conceded that any except purely private problems did not lend themselves to a political answer. That is, government could directly or indirectly alleviate any distress.” White House aide Joseph Califano later confessed, “We did not recognize that government could not do it all.” Yet to describe the War on Poverty as merely hubristic would be too kind to its promoters.

All too many of the programs fell short of even this species of defectiveness, amounting to little more than garden-variety efforts to turn taxpayer money into purely personal and political swag for the insiders who designed, operated, and exploited the programs. For example, the Community Action Program, unforgettably lampooned by Tom Wolfe in his 1970 book Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers, combined ample components of white middle-class guilt, minority shakedowns, and money thrown around basically to appease the menacing claimants who, having been invited to snatch it, resorted to whatever form of intimidation would get it for them quickest. “The money,” Conkin concludes, “often seemed to dwindle away, funding little more than the wages of [Community Action Agency] employees.”

More generally, as historian John A. Andrew notes, “Through ‘iron triangles’ and the use of clientele capture, the very objects of Great Society reforms [including the War on Poverty] all too often seized control of the process to block significant change and enhance their own interests.”

Level-headed analysts could scarcely have been shocked by this outcome. As Adam Smith long ago remarked, although the “man of system”—preeminent examples of which played leading roles in initiating the War on Poverty—treats the members of society as if they were pieces on a chessboard, the people have a motive power of their own. In the mid-1960s those whom the social and economic planners undertook to help in various ways refused to sit still while the technocrats treated them as lab rats. Instead they often reacted by resisting, diverting, or seizing control of the “top-down” schemes the government imposed on them, causing what analysts in retroactive assessments call program failures.

One man’s failed experiment, however, was often another man’s fulfilled political ambition or bulked-up bank account. Across the country, for example, local politicians diverted federal money intended to fund the War on Poverty into support for prosaic, local political priorities. Although many writers now speak of this much-ballyhooed crusade as a failure, it was a rousing success for many of its movers and shakers.

Robert Higgs

Robert Higgs is Senior Fellow in Political Economy for the Independent Institute and Editor at Large of the Institute’s quarterly journal The Independent Review.

He is a member of the FEE Faculty Network.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

Sunday, May 21, 2023

Louis Slotin and the Demon Core on This Day in History

Saturday, May 20, 2023

The Metric System on This Day in History

Friday, May 19, 2023

Communist Dictator Pol Pot on This Day in History

Thursday, May 18, 2023

Hot Wheels Toy Cars on this Day in History

Wednesday, May 17, 2023

CITGO Gas Stations on This Day in History

On this day in 1965, gasoline stations affiliated with the Cities Service Company changed their signs to reflect the new name, "CITGO", as well as a new symbol and new colors, as part of a $20,000,000 marketing changeover. Through a spokesman, the Oklahoma-based oil producer (later acquired as a subsidiary of Petróleos de Venezuela) announced that "The distance from which the new CITGO emblem and color scheme can be seen is twice that of the previous green and white Cities Service signs and stations." Stanley D. Breitweiser went on to say that the name had been chosen from "more than 80,000 possible choices" generated by a computer programmed to create new five-letter words that began with "C", and that the logo, colors and name had been developed with the assistance of the design firm of Lippincott and Marguiles. He explained that "Its first portion, CIT, is derived from Cities Service. GO implies the company's power, energy and progressive nature."

Tuesday, May 16, 2023

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn & Censorship on This Day in History

Monday, May 15, 2023

The Last Execution for Armed Robbery on This Day in History

Sunday, May 14, 2023

The Last Witchcraft Trial on This Day in History

Saturday, May 13, 2023

Mexican Crime on This Day in History

This day in history: On this day in 2012, forty-nine dismembered bodies are discovered by Mexican authorities on Mexican Federal Highway 40.

The US State Department has recently issued the following travel advisory: "Violent crime – such as homicide, kidnapping, carjacking, and robbery – is widespread and common in Mexico. The U.S. government has limited ability to provide emergency services to U.S. citizens in many areas of Mexico, as travel by U.S. government employees to certain areas is prohibited or restricted. In many states, local emergency services are limited outside the state capital or major cities."

Mexico is the 13th most dangerous place in the world to visit. The top 10 most dangerous places in the world are: El Salvador, Jamaica, Lesotho, Honduras, Belize, Venezuela, Saint Vincent And The Grenadines, South Africa, Saint Kitts And Nevis and Nigeria.

The safest places in the world are: Iceland, New Zealand, Ireland, Denmark, Austria, Portugal, Slovenia, Czech Republic, Singapore and Japan.

Friday, May 12, 2023

The Gorilla Killer on This Day in History

Thursday, May 11, 2023

Physicist Richard Feynman on This Day in History

Richard Feynman was one of the greatest physicists of the 20th century. He worked on the Manhattan Project during WWII, helped uncover the cause of NASA’s Challenger tragedy, and received the Nobel Prize for his work in quantum physics. A set of his lectures are available on Youtube – and they’re extremely approachable even for non-physicists.

I first heard about this dude while listening to the Great Courses’ Particle Physics for Non-Physicists. His name kept coming up, so naturally I had to Google him. I discovered that he had published an autobiography based on some conversations he had with a friend. The book is called Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!, and I ended up downloading it on Audible.

If you’re an academic with a resume the size of Feynman’s, I can’t help but assume you must have been an obsessive, humorless geezer. But as it turns out, Feynman was a character. The guy had a huge personality and a habit of getting into trouble. His book was thoroughly entertaining.

But the thing that delighted me most about the book was Feynman’s way of interacting with the world. He was a fun-loving guy, and everything he did was because he was curious about why things worked the way they did.

Feynman as a Tinkerer

When he was a kid, Feynman was really fascinated by radios. He played with voltages and frequencies and took apart electronics in his room all the time, sometimes even starting electrical fires (that he kept from his parents of course). Like most parents, his had a habit of “sending him outside to play” when he’d rather be tinkering and playing in his own way. But still, he tinkered on.

Gradually, he became known around his town as a bit of a handyman. At the age of 12 or so, he frequently found one-off jobs fixing people’s radios. Business was steady, even though he was doing this during the Great Depression. He gave everything a shot even when he wasn’t sure he’d be successful.

But it wasn’t just tinkering and repairing electronics that he learned in his life. After he’d already established himself as an apt physicist and professor, he learned to draw. He took lots of lessons from different people and practiced so much that he got pretty good. Really good, in fact. He was stubborn about his artwork being seen for itself and not as “a surprisingly nice drawing by a world-renowned physicist,” so instead of signing his work with his name, he used the pen name “Ofey.” He ended up selling several pieces of his art.

Feynman wasn’t all success though. He went through several bouts of depression, burnout, and imposter syndrome in his life. During one of these bouts, while bemoaning his inability to come up with any new ideas in his field, he had an insight into what was inhibiting his creativity:

Then I had another thought: Physics disgusts me a little bit now, but I used to enjoy doing physics. Why did I enjoy it? I used to play with it. I used to do whatever I felt like doing — it didn’t have to do with whether it was important for the development of nuclear physics, but whether it was interesting and amusing for me to play with. When I was in high school, I’d see water running out of a faucet growing narrower, and wonder if I could figure out what determines that curve. I found it was rather easy to do. I didn’t have to do it; it wasn’t important for the future of science; somebody else had already done it. That didn’t make any difference: I’d invent things and play with things for my own entertainment.

In the end, he decided to forget about proving himself or being brilliant. He resolved himself to just playing with physics for fun and thinking about inconsequential problems. This approach ended up soothing his burnout. And led him straight to the work that got him a Nobel Prize.

Feynman as a Role Model

The thing that I picked up from all of Feynman’s anecdotes and shenanigans is that his success stemmed from the way that he interacted with the world. Everything was interesting and fun to him. He was carefree and curious. And ultimately, he saw everything as a game. A game where the rules are knowable, yet not quite known.

I see a lot of people give advice to youngins like me about following our passions. “Do what you love,” they say. “Do what comes naturally. Do what you already have a knack for.”

But after reading Richard Feynman’s autobiography, I would rather follow the advice, “Make everything a game.”

Whatever you want to do or improve on can be turned into a game. You might not know the rules at first, but if you take up a playful attitude and persist, you’ll eventually uncover them. And once you know the rules, you can practice and play until you win.

When he lost his touch, Feynman used this “everything is a game” mindset to set himself back on the right path.

Feynman wasn’t born knowing how radios worked. He fiddled with them and learned the hard way. He stuck with his odd hobby even when his family badgered him, and even while the economy was sour. He didn’t have an innate talent for drawing either. He practiced and practiced until he got to a level where people wanted to buy his work. He taught himself how to draw (and many other things) as a grown man who had already established himself as “someone else.” And even when he lost his touch and felt like a downright loser, Feynman used this “everything is a game” mindset to set himself back on the right path.

Whether you want to learn something concrete like how to play the ukulele or how to run a business, or an abstract process like how to live a happy life, turn the whole endeavor into a game. Uncover the rules. Practice. And then play to win and achieve your goals. That’s how the great physicist Richard Feynman would have done it.

Reprinted from the author's personal blog.

Leisa Miller

Leisa Miller was a marketing coordinator at FEE. Driven by a desire for adventure, she moved to Warsaw, Poland in 2015 to work for a serial entrepreneur she met on the internet. 15 months and several hundred pierogi later, she came back to the States to hone her marketing skills at a tech startup in Charleston, South Carolina, before eventually making her way to Atlanta and joining the FEE team. In her free time, Leisa enjoys listening to 20th century classical music, learning languages, preparing Gongfu style tea, and swing dancing. You can follow her writing and personal projects on her website.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.